Caribbean super-rat history extracted from DNA

- 22 April 2015

- Science & Environment

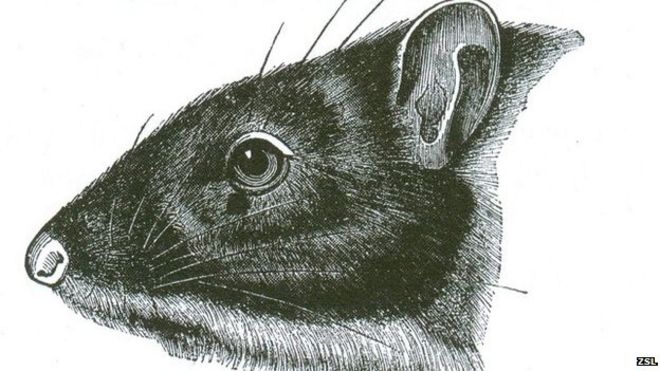

Scientists have pieced together the evolutionary history of a fascinating group of extinct Caribbean rats, some of which grew to the size of cats.

The so-called rice rats were lost from the Lesser Antilles - the likes of St Kitts and Grenada - over 100 years ago.

They were driven to oblivion by the activities of European settlers.

But now, UK researchers' DNA studies have worked out when the rodents first arrived in the islands, and how they radiated across the region.

Selina Brace, Sam Turvey and others report their work in Proceedings B, a journal of the Royal Society.

It was a tough job. Only a few examples of these rats are still held in museum collections, and the DNA material recovered from archaeological specimens tends to have degraded in the tropical heat.

Nonetheless, the team was able to find sufficient samples to map out the rodents' history.

Surprising diversity

The investigations show these creatures probably first arrived in the eastern Caribbean about six million years ago, in the late Miocene.

They would have done this on vegetation rafts, flushed out of rivers that entered the ocean on the north coast of South America.

The genetics indicate that there were at least two big dispersals of the rats, but what surprised the team was just how diverse the animals became once they arrived on the islands.

Even on St Eustatius, St Kitts and Nevis – which would have formed a single island when sea levels were lowered during glacial periods – there was unexpected genetic diversity.

"We would have expected, a priori, that the rodents on that island bank would have been basically genetically identical, because of this potential for gene flow," explained Dr Turvey, from the Zoological Society of London.

"In fact, the populations from each of those three islands were highly differentiated, potentially to the level of maybe being different species. And so it would seem the high-end estimates for how many rice rat species there were across the Caribbean – about 15-20 – are probably accurate."

This only goes to underline the scale of biodiversity loss that was initiated when human settlers arrived from Europe.

'Tremendous loss'

They changed the environment, by cutting down trees. They also brought with them brown and black rats, and, significantly, the mongoose, which was used to keep sugar plantations free of pests.

This combination of forces obliterated the rice rats from the Lesser Antilles - along with many other mammal species as well - in the space of about 200 years. The last rice rats probably died off in the very early 20th Century.

Today, researchers regard what happened in the Caribbean as one of the largest mammal extinction events in the past few thousand years. Its magnitude rivals even that seen in Australia where settlers removed a great many mammals, including the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger as it is commonly called.

"The rice rat extinction is itself a major extinction event, but it is only a component of the wider loss of mammals across the entire Caribbean basin," said Dr Turvey.

"We've been talking about just the Lesser Antilles, but in the Greater Antilles – the likes of Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, the Caymans and Puerto Rico, etc – there have been a huge number of extinctions as well.

"It's hard to know exactly how many species disappeared across the Caribbean Basin as a whole, but there were probably in the order of over 100 different, distinct island populations of endemic mammals, of which there are maybe 7-10 left. A tremendous loss of mammalian biodiversity."

.jpg)

.jpg)