Does the light off the Soul be gain a measure to the Aura of wait,

as the lift to a body is nigh the simplicity of bright,

may a mind know the brain of type?

What is the sing of an ounce as the pound to a Coin,

can a Ferry be the Main Y?

Shall the Tunnel be Vic's Sin,

as a board might be counted as the sand of grain,

is that then the dial of the clam to oyster a pearl of the see.

The operating system to masque a cent tense would speak,

in quiet on a speech is that the calf of leg or thigh of talk to Turkey a vulture on the Flight?

Shipping neet,

no ice is the glacier at the sea of a lagoon,

a rib to a kettle as the file is of grace,

may the list of schedule encourage more than a bone,

marrow is the richest tongue to Bay be that fish in the shelf of Library,

an encyclopedia at the envelope is mirror to reflect,

in chin a jaw may drop as that is not grave however it is the teeth.

Yikes inch that think to a sign not a miracle,

as the Tennant spoke to common language in bother,

is that infamous go into the light at the Elephant quatrain of Living rooms,

master a delight to no work as the Drawing room is nigh the Hours men IT.

21 grams experiment

The 21 grams experiment refers to a scientific study published in 1907 by Duncan MacDougall, a physician from Haverhill, Massachusetts. MacDougall hypothesized that souls have physical weight, and attempted to measure the mass lost by a human when the soul departed the body. MacDougall attempted to measure the mass change of six patients at the moment of death. One of the six subjects lost three-fourths of an ounce (21.3 grams).

MacDougall stated his experiment would have to be repeated many times before any conclusion could be obtained. The experiment is widely regarded as flawed and unscientific due to the small sample size, the methods used, as well as the fact only one of the six subjects met the hypothesis. The case has been cited as an example of selective reporting. Despite its rejection within the scientific community, MacDougall's experiment popularized the concept that the soul has weight, and specifically that it weighs 21 grams.

Experiment[edit]

In 1901, Duncan MacDougall, a physician from Haverhill, Massachusetts, who wished to scientifically determine if a soul had weight, identified six patients in nursing homes whose death was imminent. Four were suffering from tuberculosis, one from diabetes, and one from unspecified causes. MacDougall specifically chose people who were suffering from conditions that caused physical exhaustion, as he needed the patients to remain still when they died to measure them accurately. When the patients looked like they were close to death, their entire bed was placed on an industrial sized scale that was sensitive within two tenths of an ounce (5.6 grams).[1][2][3] On the belief that humans have souls and that animals do not, MacDougall later measured the changes in weight from fifteen dogs after death. MacDougall said he wished to use dogs that were sick or dying for his experiment, though was unable to find any. It is therefore presumed he poisoned healthy dogs.[2][4][5]

Results[edit]

One of the patients lost weight but then put the weight back on, and two of the other patients registered a loss of weight at death but a few minutes later lost even more weight. One of the patients lost "three-fourths of an ounce" (21.3 grams) in weight, coinciding with the time of death. MacDougall disregarded the results of another patient on the grounds the scales were "not finely adjusted", and discounted the results of another as the patient died while the equipment was still being calibrated. MacDougall reported that none of the dogs lost any weight after death.[3][4]

While MacDougall believed the results from his experiment showed the human soul might have weight, his report, which was not published until 1907, stated the experiment would have to be repeated many times before any conclusion could be obtained.[4][5]

Reaction[edit]

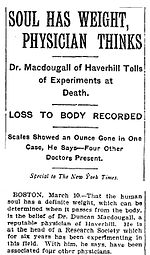

Before MacDougall was able to publish the results of his experiments, The New York Times broke the story in an article titled "Soul has Weight, Physician Thinks".[6] MacDougall's results were published in April of the same year in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research,[7] and the medical journal American Medicine.[8]

Criticism[edit]

Following the publication of the experiment in American Medicine, physician Augustus P. Clarke criticized the experiment's validity. Clarke noted that at the time of death there is a sudden rise in body temperature as the lungs are no longer cooling blood, causing a subsequent rise in sweating which could easily account for MacDougall’s missing 21 grams. Clarke also pointed out that, as dogs do not have sweat glands, they would not lose weight in this manner after death.[1][2] Clarke's criticism was published in the May issue of American Medicine. Arguments between MacDougall and Clarke debating the validity of the experiment continued to be published in the journal until at least December that year.[2]

MacDougall's experiment has been the subject of considerable skepticism, and he has been accused of both flawed methods and outright fraud in obtaining his results.[9] Noting that only one of the six patients measured supported the hypothesis, Karl Kruszelnickihas stated the experiment is a case of selective reporting, as MacDougall ignored the majority of the results. Kruszelnicki also criticized the small sample size, and questioned how MacDougall was able to determine the exact moment when a person had died considering the technology available in 1907.[3] In 2008 physicist Robert L. Park wrote that MacDougall's experiments "are not regarded today as having any scientific merit",[5]and psychologist Bruce Hood wrote that "because the weight loss was not reliable or replicable, his findings were unscientific".[9] Professor Richard Wiseman said that within the scientific community, the experiment is confined to a "large pile of scientific curiosities labelled 'almost certainly not true'".[1]

An article by Snopes in 2013 said the experiment was flawed because the methods used were suspect, the sample size was much too small, and the capability to measure weight changes too imprecise, concluding: "credence should not be given to the idea his experiments proved something, let alone that they measured the weight of the soul as 21 grams."[4] The fact that MacDougall likely poisoned and killed fifteen healthy dogs in an attempt to support his research has also been a source of criticism.[2][4]

Legacy[edit]

In 1911 The New York Times reported that MacDougall was hoping to run experiments to take photos of souls, but he appears to not have continued any further research into the area and died in 1920.[4] His experiment has not been repeated.[5]

Despite its rejection within the scientific community, MacDougall's experiment popularized the idea that the soul has weight, and specifically that it weighs 21 grams.[3][5] Most notably, '21 Grams' was taken as the title of a film in 2003, which references the experiment.[1][4][5]

The concept of a soul weighing 21 grams is mentioned in numerous media, including a 2013 issue of the manga Gantz,[10] a 2013 podcast of Welcome to Night Vale,[11] the 2015 film The Empire of Corpses,[12] and the 2015 song "21 Grams" by Niykee Heaton, which features the line "I just want your soul in my hands, feel your weight of 21 grams."[13] MacDougall and his experiments are explicitly mentioned in the 1978 documentary film Beyond and Back,[14] and episode five of the first season of Dark Matters: Twisted But True.[15] A fictional American scientist named "Mr. MacDougall" appears in Gail Carriger's 2009 novel Soulless, as an expert in the weight and measurement of souls.[16]

Smithson Tennant

Tennant is best known for his discovery of the elements iridium and osmium, which he found in the residues from the solution of platinum ores in 1803. He also contributed to the proof of the identity of diamond and charcoal. The mineral tennantite is named after him.

Contents

[hide]Life[edit]

Tennant was born in Selby in Yorkshire. His father was Calvert Tennant (named after his grandmother Phyllis Calvert, a granddaughter of Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore). His own name derives from his grandmother Rebecca Smithson, widow of Joshua Hitchling. He attended Beverley Grammar School and there is a plaque over one of the entrances to the present school commemorating his discovery of the two elements, osmium and iridium. He began to study medicine at Edinburgh in 1781, but after a few months moved to Cambridge, where he devoted himself to botany and chemistry. He graduated M.D. at Cambridge in 1796,[3] and about the same time purchased an estate near Cheddar, where he carried out agricultural experiments. He was appointed professor of chemistry at Cambridge in 1813, but lived to deliver only one course of lectures, being killed near Boulogne-sur-Mer by the fall of a bridge over which he was riding.[4][2]