International Monetary Fund

The

International Monetary Fund (

IMF) is an international organization headquartered in

Washington, D. C., of 188 countries working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world.

[1] Formed in 1944 at the

Bretton Woods Conference, it came into formal existence in 1945 with 29 member countries and the goal of reconstructing the

international payment system. Countries contribute

funds to a pool through a quota system from which countries with payment imbalances can borrow. As of 2010, the fund had

XDR476.8 billion, about US$755.7 billion at then-current exchange rates.

[2]

Through this fund, and other activities such as statistics keeping and analysis, surveillance of its members' economies and the demand for self-correcting policies, the IMF works to improve the economies of its member countries.

[3] The organization's objectives stated in the Articles of Agreement are:

[4] to promote international economic cooperation,

international trade, employment, and exchange-rate stability, including by making financial resources available to member countries to meet

balance-of-payments needs.

[5]

Functions[edit]

According to the IMF itself, it works to foster global growth and

economic stability by providing policy, advice and financing to members, by working with

developing nations to help them achieve macroeconomic stability, and by

reducing poverty.

[6] The rationale for this is that private international capital markets function imperfectly and many countries have limited access to financial markets. Such market imperfections, together with balance-of-payments financing, provide the justification for official financing, without which many countries could only correct large external payment imbalances through measures with adverse economic consequences.

[7] The IMF provides alternate sources of financing.

The IMF's role was fundamentally altered after the

floating exchange rates post 1971. It shifted to examining the economic policies of countries with IMF loan agreements to determine if a shortage of capital was due to

economic fluctuations or economic policy. The IMF also researched what types of government policy would ensure economic recovery.

[11] The new challenge is to promote and implement policy that reduces the frequency of crises among the emerging market countries, especially the middle-income countries that are vulnerable to massive capital outflows.

[12] Rather than maintaining a position of oversight of only exchange rates, their function became one of surveillance of the overall macroeconomic performance of member countries. Their role became a lot more active because the IMF now manages economic policy rather than just exchange rates.

In addition, the IMF negotiates conditions on lending and loans under their policy of

conditionality,

[8] which was established in the 1950s.

[10] Low-income countries can borrow on

concessional terms, which means there is a period of time with no interest rates, through the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), the Standby Credit Facility (SCF) and the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). Nonconcessional loans, which include interest rates, are provided mainly through

Stand-By Arrangements (SBA), the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL), and the Extended Fund Facility. The IMF provides emergency assistance via the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) to members facing urgent balance-of-payments needs.

[13]

Surveillance of the global economy[edit]

The IMF is mandated to oversee the international monetary and financial system and monitor the economic and financial policies of its member countries.

[14] This activity is known as surveillance and facilitates international cooperation.

[15] Since the demise of the

Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s, surveillance has evolved largely by way of changes in procedures rather than through the adoption of new obligations.

[14] The responsibilities changed from those of guardian to those of overseer of members’ policies.

The Fund typically analyzes the appropriateness of each member country’s economic and financial policies for achieving orderly economic growth, and assesses the consequences of these policies for other countries and for the

global economy.

[14]

IMF

Data Dissemination Systems participants:

IMF member using SDDS

IMF member using GDDS

IMF member, not using any of the DDSystems

non-IMF entity using SDDS

non-IMF entity using GDDS

no interaction with the IMF

In 1995 the International Monetary Fund began work on data dissemination standards with the view of guiding IMF member countries to disseminate their economic and financial data to the public. The International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) endorsed the guidelines for the dissemination standards and they were split into two tiers: The General Data Dissemination System (GDDS) and the

Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS).

The executive board approved the SDDS and GDDS in 1996 and 1997 respectively, and subsequent amendments were published in a revised

Guide to the General Data Dissemination System. The system is aimed primarily at

statisticians and aims to improve many aspects of statistical systems in a country. It is also part of the World Bank

Millennium Development Goals and Poverty Reduction Strategic Papers.

The primary objective of the GDDS is to encourage member countries to build a framework to improve data quality and statistical capacity building in order to evaluate statistical needs, set priorities in improving the timeliness,

transparency, reliability and accessibility of financial and economic data. Some countries initially used the GDDS, but later upgraded to SDDS.

Some entities that are not themselves IMF members also contribute statistical data to the systems:

Conditionality of loans[edit]

IMF conditionality is a set of policies or conditions that the IMF requires in exchange for financial resources.

[8] The IMF does require

collateral from countries for loans but also requires the government seeking assistance to correct its macroeconomic imbalances in the form of policy reform. If the conditions are not met, the funds are withheld.

[8] Conditionality is perhaps the most controversial aspect of IMF policies.

[17][weasel words] The concept of conditionality was introduced in a 1952 Executive Board decision and later incorporated into the Articles of Agreement.

Conditionality is associated with economic theory as well as an enforcement mechanism for repayment. Stemming primarily from the work of

Jacques Polak, the theoretical underpinning of conditionality was the "monetary approach to the balance of payments".

[10]

Structural adjustment[edit]

Some of the conditions for structural adjustment can include:

- Cutting expenditures, also known as austerity.

- Focusing economic output on direct export and resource extraction,

- Devaluation of currencies,

- Trade liberalisation, or lifting import and export restrictions,

- Increasing the stability of investment (by supplementing foreign direct investment with the opening of domestic stock markets),

- Balancing budgets and not overspending,

- Removing price controls and state subsidies,

- Privatization, or divestiture of all or part of state-owned enterprises,

- Enhancing the rights of foreign investors vis-a-vis national laws,

- Improving governance and fighting corruption.

Benefits[edit]

These loan conditions ensure that the borrowing country will be able to repay the IMF and that the country will not attempt to solve their balance-of-payment problems in a way that would negatively impact the

international economy.

[18][19] The incentive problem of

moral hazard—when

economic agents maximize their own

utility to the detriment of others because they do not bear the full consequences of their actions—is mitigated through conditions rather than providing collateral; countries in need of IMF loans do not generally possess internationally valuable collateral anyway.

[19]

Conditionality also reassures the IMF that the funds lent to them will be used for the purposes defined by the Articles of Agreement and provides safeguards that country will be able to rectify its macroeconomic and structural imbalances.

[19] In the judgment of the IMF, the adoption by the member of certain corrective measures or policies will allow it to repay the IMF, thereby ensuring that the resources will be available to support other members.

[17]

As of 2004, borrowing countries have had a very good track record for repaying credit extended under the IMF's regular lending facilities with full interest over the duration of the loan. This indicates that IMF lending does not impose a burden on creditor countries, as lending countries receive market-rate interest on most of their quota subscription, plus any of their own-currency subscriptions that are loaned out by the IMF, plus all of the reserve assets that they provide the IMF.

[7]

History[edit]

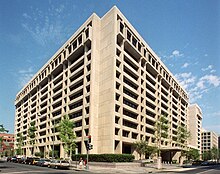

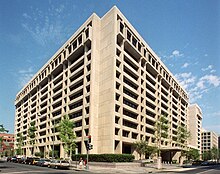

IMF "Headquarters 1" in Washington, D.C.

The IMF was originally laid out as a part of the

Bretton Woods system exchange agreement in 1944.

[20] During the

Great Depression, countries sharply raised barriers to trade in an attempt to improve their failing economies. This led to the

devaluation of national currencies and a decline in world trade.

[21]

This breakdown in international monetary co-operation created a need for oversight. The representatives of 45 governments met at the

Bretton Woods Conference in the Mount Washington Hotel in

Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the United States, to discuss a framework for postwar international economic cooperation and how to rebuild Europe.

There were two views on the role the IMF should assume as a global economic institution. British economist

John Maynard Keynesimagined that the IMF would be a coöperative fund upon which member states could draw to maintain economic activity and employment through periodic crises. This view suggested an IMF that helped governments and to act as the U.S. government had during the

New Deal in response to World War II. American delegate

Harry Dexter White foresaw an IMF that functioned more like a bank, making sure that borrowing states could repay their debts on time.

[22] Most of White's plan was incorporated into the final acts adopted at Bretton Woods.

First page of the Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund, 1 March 1946. Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives

The IMF formally came into existence on 27 December 1945, when the first 29 countries

ratified its Articles of Agreement.

[23] By the end of 1946 the IMF had grown to 39 members.

[24] On 1 March 1947, the IMF began its financial operations,

[25] and on 8 May France became the first country to borrow from it.

[24]

Plaque Commemorating the Formation of the IMF in July 1944 at the Bretton Woods Conference

The IMF was one of the key organisations of the international economic system; its design allowed the system to balance the rebuilding of international capitalism with the maximisation of national economic sovereignty and human welfare, also known as

embedded liberalism.

[26] The IMF's influence in the global economy steadily increased as it accumulated more members. The increase reflected in particular the attainment of political independence by many African countries and more recently the 1991

dissolution of the Soviet Union because most countries in the Soviet sphere of influence did not join the IMF.

[21]

The Bretton Woods system prevailed until 1971, when the U.S. government suspended the convertibility of the US$ (and dollar reserves held by other governments) into gold. This is known as the

Nixon Shock.

[21]

Since 2000[edit]

In May 2010, the IMF participated, in 3:11 proportion, in the

first Greek bailout that totalled €110 billion, to address the great accumulation of public debt, caused by continuing large public sector deficits. As part of the bailout, the Greek government agreed to adopt austerity measures that would reduce the deficit from 11% in 2009 to "well below 3%" in 2014.

[27] The bailout did not include debt restructuring measures such as a

haircut, to the chagrin of the Swiss, Brazilian, Indian, Russian, and Argentinian Directors of the IMF, with the Greek authorities themselves (at the time, PM

George Papandreou and Finance Minister

Giorgos Papakonstantinou) ruling out a haircut.

[28]

A second bailout package of more than €100 billion was agreed over the course of a few months from October 2011, during which time Papandreou was forced from office. The so-called

Troika, of which the IMF is part, are joint managers of this programme, which was approved by the Executive Directors of the IMF on 15 March 2012 for SDR23.8 billion,

[29] and which saw private bondholders take a

haircut of upwards of 50%. In the interval between May 2010 and February 2012 the private banks of Holland, France and Germany reduced exposure to Greek debt from €122 billion to €66 billion.

[28][30]

The topic of sovereign debt restructuring was taken up by the IMF in April 2013 for the first time since 2005, in a report entitled "Sovereign Debt Restructuring: Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund’s Legal and Policy Framework".

[36] The paper, which was discussed by the board on 20 May,

[37] summarised the recent experiences in Greece, St Kitts and Nevis, Belize, and Jamaica. An explanatory interview with Deputy Director Hugh Bredenkamp was published a few days later,

[38] as was a deconstruction by

Matina Stevis of the

Wall Street Journal.

[39]

In the October 2013

Financial Monitor publication, the IMF suggested that a

capital levy capable of reducing Euro-area government debt ratios to "end-2007 levels" would require a very high tax rate of about 10%.

[40]

The

Fiscal Affairs department of the IMF, headed by

Dr. Sanjeev Gupta, produced in January 2014 a report entitled "Fiscal Policy and Income Inequality" which stated that "Some taxes levied on wealth, especially on immovable property, are also an option for economies seeking more

progressive taxation...Property taxes are equitable and efficient, but underutilized in many economies...There is considerable scope to exploit this tax more fully, both as a revenue source and as a redistributive instrument."

[41]

At the end of March 2014, the IMF secured an $18 billion bailout fund for the provisional government of Ukraine in the aftermath of the

2014 Ukrainian revolution.

[42][43]

Member countries[edit]

IMF member states

IMF member states not accepting the obligations of Article VIII, Sections 2, 3, and 4

[44]

Former members are

Cuba (which left in 1964)

[48] and the

Republic of China, which was ejected from the UN in 1980 after losing the support of then U.S. President Jimmy Carter and was replaced by

the People's Republic of China.

[49] However, "Taiwan Province of China" is still listed in the official IMF indices.

[50]

Qualifications[edit]

Any country may apply to be a part of the IMF. Post-IMF formation, in the early postwar period, rules for IMF membership were left relatively loose. Members needed to make periodic membership payments towards their quota, to refrain from currency restrictions unless granted IMF permission, to abide by the Code of Conduct in the IMF Articles of Agreement, and to provide national economic information. However, stricter rules were imposed on governments that applied to the IMF for funding.

[52]

The countries that joined the IMF between 1945 and 1971 agreed to keep their exchange rates secured at rates that could be adjusted only to correct a "fundamental disequilibrium" in the balance of payments, and only with the IMF's agreement.

[53]

Some members have a very difficult relationship with the IMF and even when they are still members they do not allow themselves to be monitored. Argentina, for example, refuses to participate in an Article IV Consultation with the IMF.

[54]

Benefits[edit]

Member countries of the IMF have access to information on the economic policies of all member countries, the opportunity to influence other members’ economic policies,

technical assistance in banking, fiscal affairs, and exchange matters, financial support in times of payment difficulties, and increased opportunities for trade and investment.

[55]

Leadership[edit]

Board of Governors[edit]

The Board of Governors consists of one governor and one alternate governor for each member country. Each member country appoints its two governors. The Board normally meets once a year and is responsible for electing or appointing executive directors to the Executive Board. While the Board of Governors is officially responsible for approving quota increases,

Special Drawing Right allocations, the admittance of new members, compulsory withdrawal of members, and amendments to the Articles of Agreement and By-Laws, in practice it has delegated most of its powers to the IMF's Executive Board.

[56]

The Board of Governors is advised by the

International Monetary and Financial Committee and the

Development Committee. The International Monetary and Financial Committee has 24 members and monitors developments in global liquidity and the transfer of resources to developing countries.

[57] The Development Committee has 25 members and advises on critical development issues and on financial resources required to promote economic development in developing countries. They also advise on trade and environmental issues.

[57]

Executive Board[edit]

24 Executive Directors make up Executive Board. The Executive Directors represent all 188 member countries in a geographically based roster.

[58] Countries with large economies have their own Executive Director, but most countries are grouped in constituencies representing four or more countries.

[56]

Following the

2008 Amendment on Voice and Participation which came into effect in March 2011,

[59] eight countries each appoint an Executive Director: the

United States, Japan, Germany, France, the UK, China, the Russian Federation, and Saudi Arabia.

[58] The remaining 16 Directors represent constituencies consisting of 4 to 22 countries. The Executive Director representing the largest constituency of 22 countries accounts for 1.55% of the vote.

[citation needed] This Board usually meets several times each week.

[60] The Board membership and constituency is scheduled for periodic review every eight years.

[2]

List of Executive Directors of the IMF, as of April 2015

[show]

Managing Director[edit]

The IMF is led by a managing director, who is head of the staff and serves as Chairman of the Executive Board. The managing director is assisted by a First Deputy managing director and three other Deputy Managing Directors.

[56] Historically the IMF's managing director has been European and the president of the World Bank has been from the United States. However, this standard is increasingly being questioned and competition for these two posts may soon open up to include other qualified candidates from any part of the world.

[61][62]

In 2011 the world's largest developing countries, the

BRIC nations, issued a statement declaring that the tradition of appointing a European as managing director undermined the legitimacy of the IMF and called for the appointment to be merit-based.

[62][63]

| Nr | Dates | Name | Nationality | Background |

|---|

| 11 | 5 July 2011 – Present | Christine Lagarde |  France France | Law, Politician, Minister of Finance |

| – | 18 May 2011 – 4 July 2011 | John Lipsky acting |  United States United States | Economics, First Deputy Managing Director IMF |

| 10 | 1 November 2007 – 18 May 2011 | Dominique Strauss-Kahn |  France France | Economics, Law, Politician, Minister of the Economy and Finance |

| 9 | 7 June 2004 – 31 October 2007 | Rodrigo Rato |  Spain Spain | Law, MBA, Politician, Minister of the Economy |

| 8 | 1 May 2000 – 4 March 2004 | Horst Köhler |  Germany Germany | Economics, EBRD |

| 7 | 16 January 1987 – 14 February 2000 | Michel Camdessus |  France France | Economics, Central Banker |

| 6 | 18 June 1978 – 15 January 1987 | Jacques de Larosière |  France France | Civil Servant |

| 5 | 1 September 1973 – 18 June 1978 | Johan Witteveen |  Netherlands Netherlands | Economics, Academic, Author, Politician, Minister of Finance, Deputy Prime Minister,CPB |

| 4 | 1 September 1963 – 31 August 1973 | Pierre-Paul Schweitzer |  France France | Law, Central Banker, Civil Servant |

| 3 | 21 November 1956 – 5 May 1963 | Per Jacobsson |  Sweden Sweden | Law, Economics, League of Nations, BIS |

| 2 | 3 August 1951 – 3 October 1956 | Ivar Rooth |  Sweden Sweden | Law, Central Banker |

| 1 | 6 May 1946 – 5 May 1951 | Camille Gutt |  Belgium Belgium | Politician, Minister of Finance |

On 28 June 2011,

Christine Lagarde was named managing director of the IMF, replacing Dominique Strauss-Kahn.

Previous managing director

Dominique Strauss-Kahn was arrested in connection

with charges of sexually assaulting a New York hotel room attendant and resigned on 18 May.

[64] On 28 June 2011

Christine Lagarde was confirmed as managing director of the IMF for a five-year term starting on 5 July 2011.

[65][66] In 2012, Lagarde was paid a tax-exempt salary of US$467,940, and this is automatically increased every year according to inflation. In addition, the director receives an allowance of US$83,760 and additional expenses for entertainment.

[67]

Voting power[edit]

Voting power in the IMF is based on a quota system. Each member has a number of

basic votes (each member's number of basic votes equals 5.502% of the

total votes),

[68] plus one additional vote for each Special Drawing Right (SDR) of 100,000 of a member country's quota.

[69] The

Special Drawing Right is the unit of account of the IMF and represents a claim to currency. It is based on a basket of key international currencies. The basic votes generate a slight bias in favour of small countries, but the additional votes determined by SDR outweigh this bias.

[69]

| The table below shows quota and voting shares for IMF members (Attention: Amendment on Voice and Participation, and of subsequent reforms of quotas and governance which were agreed in 2010 but are not yet in effect.[70]) |

|---|

|

| 1 |  United States United States | 42,122.4 | 17.69 | Jacob J. Lew | Janet Yellen | 421,961 | 16.75 |

| 2 |  Japan Japan | 15,628.5 | 6.56 | Taro Aso | Haruhiko Kuroda | 157,022 | 6.23 |

| 3 |  Germany Germany | 14,565.5 | 6.12 | Jens Weidmann | Wolfgang Schäuble | 146,392 | 5.81 |

| 4 |  France France | 10,738.5 | 4.51 | Michel Sapin | Christian Noyer | 108,122 | 4.29 |

| 5 |  United Kingdom United Kingdom | 10,738.5 | 4.51 | George Osborne | Mark Carney | 108,122 | 4.29 |

| 6 |  China China | 9,525.9 | 4.00 | Zhou Xiaochuan | Gang Yi | 95,996 | 3.81 |

| 7 |  Italy Italy | 7,882.3 | 3.31 | Pier Carlo Padoan | Ignazio Visco | 79,560 | 3.16 |

| 8 |  Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabia | 6,985.5 | 2.93 | Ibrahim A. Al-Assaf | Fahad Almubarak | 70,592 | 2.80 |

| 9 |  Canada Canada | 6,369.2 | 2.67 | Joe Oliver | Stephen Poloz | 64,429 | 2.56 |

| 10 |  Russia Russia | 5,945.4 | 2.50 | Anton Siluanov | Elvira S. Nabiullina | 60,191 | 2.39 |

| 11 |  India India | 5,821.5 | 2.44 | Arun Jaitley | Raghuram Rajan | 58,952 | 2.34 |

| 12 |  Netherlands Netherlands | 5,162.4 | 2.17 | Klaas Knot | Hans Vijlbrief | 52,361 | 2.08 |

| 13 |  Belgium Belgium | 4,605.2 | 1.93 | Luc Coene | Marc Monbaliu | 46,789 | 1.86 |

| 14 |  Brazil Brazil | 4,250.5 | 1.79 | Joaquim Levy | Alexandre Antonio Tombini | 43,242 | 1.72 |

| 15 |  Spain Spain | 4,023.4 | 1.69 | Luis de Guindos | Luis M. Linde | 40,971 | 1.63 |

| 16 |  Mexico Mexico | 3,625.7 | 1.52 | Luis Videgaray | Agustín Carstens | 36,994 | 1.47 |

| 17 |  Switzerland Switzerland | 3,458.5 | 1.45 | Thomas Jordan | Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf | 35,322 | 1.40 |

| 18 |  South Korea South Korea | 3,366.4 | 1.41 | Choi Kyoung-hwan | Juyeol Lee | 34,401 | 1.37 |

| 19 |  Australia Australia | 3,236.4 | 1.36 | Joe Hockey | Martin Parkinson | 33,101 | 1.31 |

| 20 |  Venezuela Venezuela | 2,659.1 | 1.12 | Nelson José Merentes Diaz | Julio Cesar Viloria Sulbaran | 27,328 | 1.08 |

| 21 |  Sweden Sweden | 2,395.5 | 1.01 | Stefan Ingves | Mikael Lundholm | 24,692 | 0.98 |

| 22 |  Argentina Argentina | 2,117.1 | 0.89 | Axel Kicillof | Alejandro Vanoli | 21,908 | 0.87 |

| 23 |  Austria Austria | 2,113.9 | 0.89 | Ewald Nowotny | Andreas Ittner | 21,876 | 0.87 |

| 24 |  Indonesia Indonesia | 2,079.3 | 0.87 | Agus D.W. Martowardojo | Mahendra Siregar | 21,530 | 0.85 |

| 25 |  Denmark Denmark | 1,891.4 | 0.79 | Lars Rohde | Sophus Garfiel | 19,651 | 0.78 |

| 26 |  Norway Norway | 1,883.7 | 0.79 | Øystein Olsen | Svein Gjedrem | 19,574 | 0.78 |

| 27 |  South Africa South Africa | 1,868.5 | 0.78 | Pravin J. Gordhan | Gill Marcus | 19,422 | 0.77 |

| 28 |  Malaysia Malaysia | 1,773.9 | 0.74 | Najib Razak | Zeti Akhtar Aziz | 18,476 | 0.73 |

| 29 |  Nigeria Nigeria | 1,753.2 | 0.74 | Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala | Godwin Ifeanyi Emefiele | 18,269 | 0.73 |

| 30 |  Poland Poland | 1,688.4 | 0.71 | Mateusz Szczurek | Jacek Dominik | 17,621 | 0.70 |

| The rest of 158 countries | 47,844.9 | 20.11 | respective | respective | 594,895 | 23.59 |

|

Effects of the quota system[edit]

The IMF's quota system was created to raise funds for loans.

[71] Each IMF member country is assigned a quota, or contribution, that reflects the country's relative size in the global economy. Each member's quota also determines its relative voting power. Thus, financial contributions from member governments are linked to voting power in the organisation.

[69]

This system follows the logic of a shareholder-controlled organisation: wealthy countries have more say in the making and revision of rules.

[72] Since decision making at the IMF reflects each member's relative economic position in the world, wealthier countries that provide more money to the IMF have more influence than poorer members that contribute less; nonetheless, the IMF focuses on redistribution.

[69]

Developing countries[edit]

Quotas are normally reviewed every five years and can be increased when deemed necessary by the Board of Governors. Currently, reforming the representation of

developing countries within the IMF has been suggested.

[69] These countries' economies represent a large portion of the global economic system but this is not reflected in the IMF's decision making process through the nature of the quota system.

Joseph Stiglitz argues, "There is a need to provide more effective voice and representation for developing countries, which now represent a much larger portion of world economic activity since 1944, when the IMF was created."

[73] In 2008, a number of quota reforms were passed including shifting 6% of quota shares to dynamic emerging markets and developing countries.

[74]

United States influence[edit]

A second criticism is that the United States' transition to

neoliberalism and global capitalism also led to a change in the identity and functions of international institutions like the IMF. Because of the high involvement and voting power of the United States, the global economic ideology could effectively be transformed to match that of the United States. This is consistent with the IMF's function change during the 1970s after the

Nixon Shock ended the

Bretton Woods system. Allies of the United States are said to receive bigger loans with fewer conditions.

[20]

Overcoming borrower/creditor divide[edit]

The IMF's membership is divided along income lines: certain countries provide the financial resources while others use these resources. Both

developed country "creditors" and

developing country "borrowers" are members of the IMF. The developed countries provide the financial resources but rarely enter into IMF loan agreements; they are the creditors. Conversely, the developing countries use the lending services but contribute little to the pool of money available to lend because their quotas are smaller; they are the borrowers. Thus, tension is created around governance issues because these two groups, creditors and borrowers, have fundamentally different interests.

[69]

The criticism is that the system of voting power distribution through a quota system institutionalises borrower subordination and creditor dominance. The resulting division of the IMF's membership into borrowers and non-borrowers has increased the controversy around conditionality because the borrowers are interested in increasing loan access while creditors want to maintain reassurance that the loans will be repaid.

[75]

A recent source reveals that the average overall use of IMF credit per decade increased, in real terms, by 21% between the 1970s and 1980s, and increased again by just over 22% from the 1980s to the 1991–2005 period. Another study has suggested that since 1950 the continent of Africa alone has received $300 billion from the IMF, the World Bank, and affiliate institutions.

[76]

A study by Bumba Mukherjee found that developing

democratic countries benefit more from IMF programs than developing

autocratic countries because policy-making, and the process of deciding where loaned money is used, is more transparent within a democracy.

[76] One study done by

Randall Stone found that although earlier studies found little impact of IMF programs on balance of payments, more recent studies using more sophisticated methods and larger samples "usually found IMF programs improved the balance of payments".

[20]

Exceptional Access Framework – Sovereign Debt[edit]

The

Exceptional Access Framework was created in 2003 when

John B. Taylor was Under Secretary of the

U.S. Treasury for International Affairs. The new Framework became fully operational in February 2003 and it was applied in the subsequent decisions on Argentina and Brazil.

[77] Its purpose was to place some sensible rules and limits on the way the IMF makes loans to support governments with debt problem—especially in emerging markets—and thereby move away from the bailout mentality of the 1990s. Such a reform was essential for ending the crisis atmosphere that then existed in emerging markets. The reform was closely related to, and put in place nearly simultaneously with, the actions of several emerging market countries to place

collective action clauses in their bond contracts.

In 2010, the framework was abandoned so the IMF could make loans to Greece in an unsustainable and political situation.

[78][79]

The topic of sovereign debt restructuring was taken up by IMF staff in April 2013 for the first time since 2005, in a report entitled "Sovereign Debt Restructuring: Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund's Legal and Policy Framework".

[36] The paper, which was discussed by the board on 20 May,

[37] summarised the recent experiences in Greece, St Kitts and Nevis, Belize and Jamaica. An explanatory interview with Deputy Director

Hugh Bredenkamp was published a few days later,

[38] as was a deconstruction by

Matina Stevis of the

Wall Street Journal.

[39]

The staff was directed to formulate an updated policy, which was accomplished on 22 May 2014 with a report entitled "The Fund's Lending Framework and Sovereign Debt: Preliminary Considerations", and taken up by the Executive Board on 13 June.

[80] The staff proposed that "in circumstances where a (Sovereign) member has lost market access and debt is considered sustainable...the IMF would be able to provide Exceptional Access on the basis of a debt operation that involves an extension of maturities", which was labelled a "reprofiling operation". These reprofiling operations would "generally be less costly to the debtor and creditors—and thus to the system overall—relative to either an upfront debt reduction operation or a bail-out that is followed by debt reduction... (and) would be envisaged only when both (a) a member has lost market access and (b) debt is assessed to be sustainable, but not with high probability...Creditors will only agree if they understand that such an amendment is necessary to avoid a worse outcome: namely, a default and/or an operation involving debt reduction...

Collective action clauses, which now exist in most—but not all—bonds, would be relied upon to address collective action problems."

[80]

IMF and globalization[edit]

Globalization encompasses three institutions: global financial markets and

transnational companies, national governments linked to each other in economic and military alliances led by the United States, and rising "global governments" such as

World Trade Organization (WTO), IMF, and

World Bank.

[81] Charles Derber argues in his book

People Before Profit, "These interacting institutions create a new global power system where sovereignty is globalized, taking power and constitutional authority away from nations and giving it to global markets and international bodies".

[81] Titus Alexander argues that this system institutionalises global inequality between western countries and the Majority World in a form of

global apartheid, in which the IMF is a key pillar.

[82]

The establishment of globalised economic institutions has been both a symptom of and a stimulus for globalization. The development of the World Bank, the IMF

regional development banks such as the

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and multilateral trade institutions such as the WTO signals a move away from the dominance of the state as the exclusive unit of analysis in international affairs. Globalization has thus been transformative in terms of a reconceptualising of

state sovereignty.

[83]

Following U.S. President

Bill Clinton's administration's aggressive financial

deregulation campaign in the 1990s, globalisation leaders overturned longstanding restrictions by governments that limited foreign ownership of their banks, deregulated currency exchange, and eliminated restrictions on how quickly money could be withdrawn by foreign investors.

[81]

Fund report in May 2015, the world's governments indirectly subsidize fossil fuel companies with $5.3tn (£3.4tn) a year. Most this is due to polluters not paying the costs imposed on governments by the burning of coal, oil and gas: air pollution, health problems, the floods, droughts and storms driven by climate change.

[84]

Criticisms[edit]

- Developed countries were seen to have a more dominant role and control over less developed countries (LDCs).

- Secondly, the Fund worked on the incorrect assumption that all payments disequilibria were caused domestically. The Group of 24 (G-24), on behalf of LDC members, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) complained that the IMF did not distinguish sufficiently between disequilibria with predominantly external as opposed to internal causes. This criticism was voiced in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis. Then LDCs found themselves with payments deficits due to adverse changes in their terms of trade, with the Fund prescribing stabilisation programmes similar to those suggested for deficits caused by government over-spending. Faced with long-term, externally generated disequilibria, the G-24 argued for more time for LDCs to adjust their economies.

- Some IMF policies may be anti-developmental; the report said that deflationary effects of IMF programmes quickly led to losses of output and employment in economies where incomes were low and unemployment was high. Moreover, the burden of the deflation is disproportionately borne by the poor.

- Lastly is the suggestion that the IMF's policies lack a clear economic rationale. Its policy foundations were theoretical and unclear due to differing opinions and departmental rivalries whilst dealing with countries with widely varying economic circumstances.

ODI conclusions were that the IMF's very nature of promoting market-oriented approaches attracted unavoidable criticism. On the other hand, the IMF could serve as a scapegoat while allowing governments to blame international bankers. The ODI conceded that the IMF was insensitive to political aspirations of LDCs, while its policy conditions were inflexible.

[86]

Argentina, which had been considered by the IMF to be a model country in its compliance to policy proposals by the

Bretton Woods institutions, experienced a catastrophic economic crisis in 2001,

[87] which some believe to have been caused by IMF-induced budget restrictions—which undercut the government's ability to sustain national infrastructure even in crucial areas such as health, education, and security—and privatisation of strategically vital national resources.

[88] Others attribute the crisis to Argentina's misdesigned fiscal federalism, which caused subnational spending to increase rapidly.

[89] The crisis added to widespread hatred of this institution in

Argentinaand other South American countries, with many blaming the IMF for the region's economic problems. The current—as of early 2006—trend toward moderate left-wing governments in the region and a growing concern with the development of a regional economic policy largely independent of big business pressures has been ascribed to this crisis.

In an interview, the former Romanian Prime Minister

Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu claimed that "Since 2005, IMF is constantly making mistakes when it appreciates the country's economic performances".

[90] Former

Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, who claimed that debt-ridden African states were ceding sovereignty to the IMF and the World Bank, famously asked, "Who elected the IMF to be the ministry of finance for every country in the world?"

[91][92]

Conditionality[edit]

The IMF has been criticised for being "out of touch" with local economic conditions, cultures, and environments in the countries they are requiring policy reform.

[8] The economic advice the IMF gives might not always take into consideration the difference between what spending means on paper and how it is felt by citizens.

[93]

Jeffrey Sachs argues that the IMF's "usual prescription is 'budgetary belt tightening to countries who are much too poor to own belts'".

[93] Sachs

[Or who says it?] wrote that the IMF's role as a generalist institution specialising in macroeconomic issues needs reform.

Conditionality has also been criticised because a country can pledge collateral of "acceptable assets" to obtain waivers—if one assumes that all countries are able to provide "acceptable collateral".

[19]

One view is that conditionality undermines domestic political institutions.

[94] The recipient governments are sacrificing policy autonomy in exchange for funds, which can lead to public resentment of the local leadership for accepting and enforcing the IMF conditions. Political instability can result from more leadership turnover as political leaders are replaced in electoral backlashes.

[8] IMF conditions are often criticised for reducing government services, thus increasing unemployment.

[10]

Another criticism is that IMF programs are only designed to address poor governance, excessive government spending, excessive government intervention in markets, and too much state ownership.

[93] This assumes that this narrow range of issues represents the only possible problems; everything is standardised and differing contexts are ignored.

[93] A country may also be compelled to accept conditions it would not normally accept had they not been in a financial crisis in need of assistance.

[17]

On top of that, regardless of what methodologies and data sets used, it comes to same conclusion of exacerbating income inequality. With

Gini coefficient, it became clear that countries with IMF programs face increased income inequality.

[95]

It is claimed that

conditionalities retard social stability and hence inhibit the stated goals of the IMF, while Structural Adjustment Programs lead to an increase in poverty in recipient countries.

[96] The IMF sometimes advocates “

austerity programmes”, cutting public spending and increasing taxes even when the economy is weak, to bring budgets closer to a balance, thus reducing

budget deficits. Countries are often advised to lower their corporate tax rate. In

Globalization and Its Discontents,

Joseph E. Stiglitz, former chief economist and senior vice-president at the

World Bank, criticizes these policies.

[97] He argues that by converting to a more

monetarist approach, the purpose of the fund is no longer valid, as it was designed to provide funds for countries to carry out

Keynesian reflations, and that the IMF "was not participating in a conspiracy, but it was reflecting the interests and ideology of the Western financial community".

[98]

International politics play an important role in IMF decision making. The clout of member states is roughly proportional to its contribution to IMF finances. The United States has the greatest number of votes and therefore wields the most influence. Domestic politics often come into play, with politicians in developing countries using conditionality to gain leverage over the opposition in order to influence policy.

[99]

Function and policies[edit]

Jeffrey Sachs argues in

The End of Poverty that the IMF and the World Bank have "the brightest economists and the lead in advising poor countries on how to break out of poverty, but the problem is development economics".

[93] Development economics needs the reform, not the IMF. He also notes that IMF loan conditions should be paired with other reforms—e.g., trade reform in

developed nations,

debt cancellation, and increased financial assistance for investments in

basic infrastructure.

[93] IMF loan conditions cannot stand alone and produce change; they need to be partnered with other reforms or other conditions as applicable.

U.S. dominance and voting reform[edit]

The scholarly consensus is that IMF decision-making is not simply technocratic, but also guided by political and economic concerns.

[100] The United States is the IMF's most powerful member, and its influence reaches even into decision-making concerning individual loan agreements.

[101] The North American giant is openly opposed to losing what Treasury Secretary

Jacob Lew describes as its "leadership role" at the IMF, "our ability to shape international norms and practices."

[102]

Reforms to give more powers to emerging economies were agreed by the

G20 in 2010; however, they are yet to be ratified by the

U.S. Congress.

[103][104][105] The 2010 reforms cannot pass without American approval, since 85% of the Fund's voting power is required,

[106] and the Americans hold more than 16% of voting power.

[107] The U.S. executive board veto was brought up again by IMF junior members in April 2014, who also expressed their ongoing frustration with U.S. failure to ratify the 2010 reforms. Singaporean Finance Minister and IMF steering committee chairman

Tharman Shanmugaratnam said it could cause "disruptive change" in the global economy: "We are more likely over time to see a weakening of multilateralism, the emergence of regionalism, bilateralism and other ways of dealing with global problems", and that would make the world a "less safe" place.

[108] In May 2015, the Obama administration made clear it would not sacrifice its IMF veto, even in order to bypass Congressional approval.

[109]

Support of military dictatorships[edit]

An example of IMF's support for a dictatorship was its ongoing support for

Mobutu's rule in

Zaire, although its own envoy,

Erwin Blumenthal, provided a sobering report about the entrenched corruption and embezzlement and the inability of the country to pay back any loans.

[110]

Arguments in favour of the IMF say that economic stability is a precursor to democracy; however, critics highlight various examples in which democratised countries fell after receiving IMF loans.

[111]

Impact on access to food[edit]

A number of

civil society organisations

[112] have criticised the IMF's policies for their impact on access to food, particularly in developing countries. In October 2008, former U.S. president

Bill Clinton delivered a speech to the United Nations on

World Food Day, criticizing the World Bank and IMF for their policies on food and agriculture:

We need the World Bank, the IMF, all the big foundations, and all the governments to admit that, for 30 years, we all blew it, including me when I was president. We were wrong to believe that food was like some other product in international trade, and we all have to go back to a more responsible and sustainable form of agriculture.

—Former U.S. president Bill Clinton,

Speech at United Nations World Food Day, October 16, 2008[113]

Impact on public health[edit]

A 2009 study concluded that the strict conditions resulted in thousands of deaths in Eastern Europe by

tuberculosis as

public health care had to be weakened. In the 21 countries to which the IMF had given loans,

tuberculosis deaths rose by 16.6%.

[114]

In 2009, a book by Rick Rowden titled

The Deadly Ideas of Neoliberalism: How the IMF has Undermined Public Health and the Fight Against AIDS, claimed that the IMF’s monetarist approach towards prioritising price stability (low inflation) and fiscal restraint (low budget deficits) was unnecessarily restrictive and has prevented developing countries from scaling up long-term investment in public health infrastructure. The book claimed the consequences have been chronically underfunded public health systems, leading to demoralising working conditions that have fuelled a "

brain drain" of medical personnel, all of which has undermined public health and the fight against

HIV/AIDS in developing countries.

[115]

Impact on environment[edit]

IMF policies have been repeatedly criticised for making it difficult for indebted countries to say no to environmentally harmful projects that nevertheless generate revenues such as oil, coal, and forest-destroying lumber and agriculture projects.

Ecuador for example had to defy IMF advice repeatedly to pursue the protection of its

rain forests, though paradoxically this need was cited in IMF argument to support that country. The IMF acknowledged this paradox in the 2010 report that proposed the IMF Green Fund, a mechanism to issue

special drawing rights directly to pay for climate harm prevention and potentially other ecological protection as pursued generally by other

environmental finance.

[116]

While the response to these moves was generally positive

[117] possibly because ecological protection and energy and infrastructure transformation are more politically neutral than pressures to change social policy. Some experts voiced concern that the IMF was not representative, and that the IMF proposals to generate only US$200 billion a year by 2020 with the SDRs as seed funds, did not go far enough to undo the general incentive to pursue destructive projects inherent in the world commodity trading and banking systems—criticisms often levelled at the

World Trade Organization and large global banking institutions.

In the context of the

European debt crisis, some observers noted that Spain and California, two troubled economies within Europe and the United States, and also Germany, the primary and politically most fragile supporter of a

euro currency bailout would benefit from IMF recognition of their leadership in

green technology, and directly from Green Fund–generated demand for their exports, which could also improve their

credit ratings.

[citation needed]

Alternatives[edit]

In the media[edit]

Life and Debt, a documentary film, deals with the IMF's policies' influence on

Jamaica and its economy from a critical point of view.

Debtocracy, a 2011 independent Greek documentary film, also criticizes the IMF. Portuguese musician

José Mário Branco's 1982 album

FMI is inspired by the IMF's intervention in Portugal through monitored stabilization programs in 1977–78.