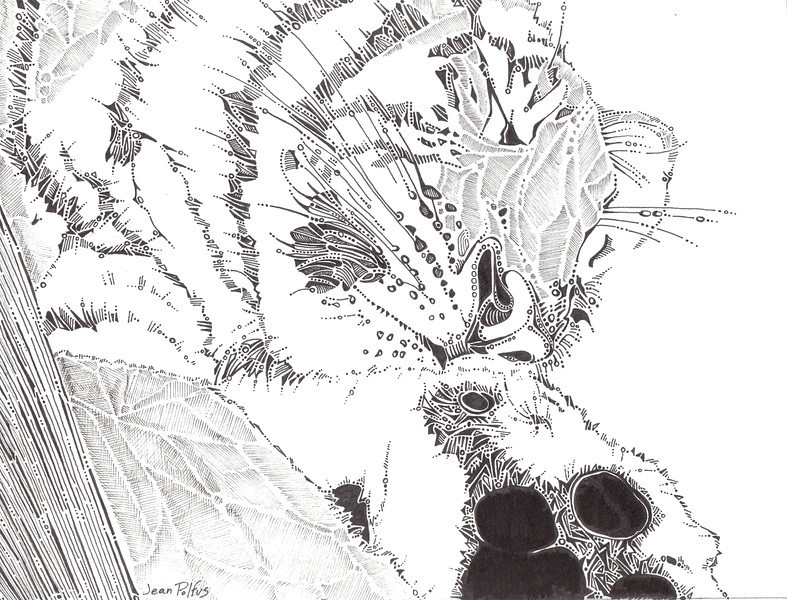

Jean Polfus has found a fairly creative way to combine the aim of ecology with the impact of art.

Jean Polfus collecting *Grizzly Hair in Atlin BC, summer 2009 from a **Barbed wire fence.

Jean Polfus

Bridging The Gap Between Ecology & Art

October 1st, 2014

Jean Polfus has found a fairly creative way to combine the aim of ecology with the impact of art.

Jean is an artist, but that’s not her full-time job. She’s actually an ecologist, who looks at the ecosystem and inhabitants of the Northwest Territories in Canada. It’s how she connects creative thinking in art and the science-minded attitude behind ecology that is surprising.

After a traditional path of pursuing evolutionary and environmental biology at Dartmouth College, Jean came to discover that working with the various cultures and languages of her studies presented a unique problem. How do you bridge the communication gaps as well as beliefs of tribes, scientists, and the needs of animals and their systems?

Jean realized that art – specifically drawing and photography – is one answer:

“One of my goals is to find innovative ways to bring art and science together through drawings, explanations, illustrations and photography. Though many similarities exist between artists and scientists, I have found that there is a fundamental lack of visual creative thinking in academia. This problem is apparent on all levels of scientific exploration, starting with the initial conception of a project to exchange with other academics, and of course worst of all, communication with the general public.”

“One of my goals is to find innovative ways to bring art and science together through drawings, explanations, illustrations and photography.”

To empower the science behind her work, Jean introduces drawings and paintings into her presentations and brainstorming sessions.

When the people she meets with during her work either don’t speak the language or are leaning too far down a scientific mindset or a historic (or cultural) one, the ability to draw allows everyone to meet in the middle and see the same picture. It’s an effective way of communicating ideas without losing their meaning. In-fact, Jean explains, drawing and presenting photos often develops ideas further.

Using artwork to present concepts and bridge communication gaps has greatly benefited Jean and her work. It’s the type of creative thinking that seems like a no-brainer once you know of it, but (as she’s pointed out) is still very absent in scientific academia and exploration.

“I have learned that appealing visuals have the potential to help local people, who are most affected by management decisions, depict their own understanding about wildlife and understand the western scientific data and results that affect their way of life.”

Jean also explains how her ability to present data in visual formats makes taking action on the information easier:

“I’ve had very good success with using informational graphics to explain the genetic side of my research to the community. Over time I’ve developed better analogies to use as well as clearer visuals that help describe genetic relationships. This has been a crucial part of my research because I want people to understand why I am doing the research and feel confident enough to provide suggestions for how I can improve my sample collection methods and the interpretation of the genetic results.”

Creativity isn’t about art: it’s about using different concepts to bridge the gaps in communication or thinking.

Jean Polfus has done just that by combining her research with her love for art. The result is effective communication and better understanding by those she works closely with and for.

How can you use Jean as an example in order to combine approaches that are usually polar opposites in order to generate creative insights?

Learn more about Jean and her work right here, and follow her on Tumblr at jeanpolfus.tumblr.com.

Written by Tanner Christensen

http://creativesomething.net/post/98904073510/jean-polfus-bridging-the-gap-between-ecology-and

*Grizzly bear

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Grizzly bear (disambiguation).

"Grizzly" redirects here. For other uses, see Grizzly (disambiguation).

| Grizzly bear | |

|---|---|

| |

| Grizzly bear | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Ursidae |

| Genus: | Ursus |

| Species: | U. arctos ssp. |

| Binomial name | |

| Ursus arctos (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

| |

| Historic and present range | |

The grizzly bear (Ursus arctos ssp.) is any North American morphological form or subspecies of brown bear, including the mainlandgrizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis), Kodiak bear (U. a. middendorffi), peninsular grizzly (U. a. gyas), and the recently extinct California grizzly (U. a. californicus†)[1][2] and Mexican grizzly bear (U. a. nelsoni†). Scientists do not use the name grizzly bear but call it the North American brown bear. (See brown bear for a discussion of brown bears outside of North America). It should not be confused with the black grizzly or Ussuri brown bear (U. a. lasiotus) which is another giant brown bear inhabiting Russia, Northern China, and Korea.[3][4][5]

Contents

[hide]Classification[edit]

Meaning of "grizzly"[edit]

Lewis & Clark named it to be grisley or "grizzly", which could have meant "grizzled"; that is, golden and grey tips of the hair or "fear-inspiring".[6] Nonetheless, after careful study, naturalist George Ord formally classified it in 1815 – not for its hair, but for its character – asUrsus horribilis ("terrifying bear").[7]

Evolution and genetics[edit]

Grizzly phylogenetics[edit]

Classification has been revised along genetic lines.[1] There are two morphological forms of Ursus arctos, the grizzly and the coastal brown bears, but these morphological forms do not have distinct mtDNA lineages.[8]

Ursus arctos - the brown bear[edit]

Brown bears originated in Eurasia and traveled to North America approximately 50,000 years ago,[9][10] spreading into the contiguous United States about 13,000 years ago.[11] In the 19th century, the grizzly was classified as 86 distinct species. However, by 1928 only seven grizzlies remained[2] and by 1953 only one species remained globally.[12] However, modern genetic testing reveals the grizzly to be a subspecies of the brown bear (Ursus arctos). Rausch found that North America has but one species of grizzly.[13] Therefore, everywhere it is the "brown bear"; in North America, it is the "grizzly", but these are all the same species, Ursus arctos.

Ursus arctos subspecies in North America[edit]

In 1963 Rausch reduced the number of North American subspecies to one, Ursus arctos middendorffi[14]

Further testing of Y-chromosomes is required to yield an accurate new taxonomy with different subspecies.[1]

Coastal grizzlies, often referred to by the popular but geographically redundant synonym of "brown bear" or "Alaskan brown bear" are larger and darker than inland grizzlies, which is why they, too, were considered a different species from grizzlies. Kodiak grizzly bears were also at one time considered distinct. Therefore at one time there were five different "species" of brown bear, including three in North America.[15]

Appearance[edit]

Most adult female grizzlies weigh 130–180 kg (290–400 lb), while adult males weigh on average 180–360 kg (400–790 lb). Average total length in this subspecies is 198 cm (6.50 ft), with an average shoulder height of 102 cm (3.35 ft) and hindfoot length of 28 cm (11 in).[16] Newborn bears may weigh less than 500 grams (1.1 lb). In the Yukon Riverarea, mature female grizzlies can weigh as little as 100 kg (220 lb). One study found that the average weight for an inland male grizzly was around 272 kilograms (600 lb) and the average weight for a coastal male was around 408 kilograms (900 lb). For a female, these average weights would be 136 kilograms (300 lb) inland and 227 kilograms (500 lb) coastal, respectively.[17] On the other hand, an occasional huge male grizzly has been recorded which greatly exceeds ordinary size, with weights reported up to 680 kg (1,500 lb).[18] A large coastal male of this size may stand up to 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall on its hind legs and be up to 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) at the shoulder.[19]

Although variable in color from blond to nearly black, grizzly bear fur is typically brown with darker legs and commonly white or blond tipped fur on the flank and back.[20] A pronounced hump appears on their shoulders; the hump is a good way to distinguish a grizzly bear from a black bear, as black bears do not have this hump. Aside from the distinguishing hump a grizzly bear can be identified by a "dished in" profile of their face with short, rounded ears, whereas a black bear has a straight face profile and longer ears.[21] A grizzly bear can also be identified by its rump, which is lower than its shoulders, while a black bear's rump is higher.[21] A grizzly bear's front claws measure about 2-4 inches in length and a black bear's measure about 1-2 inches in length.[21]

Range and population[edit]

Brown bears are found in Asia, Europe, and North America, giving them the widest ranges of bear species.[2] They also inhabited North Africa and the Middle East.[22] In North America, grizzly bears previously ranged from Alaska down to Mexico and as far east as the western shores of Hudson Bay;[9] the species is now found in Alaska, south through much of western Canada, and into portions of thenorthwestern United States (including Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Wyoming), extending as far south as Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. It is most commonly found in Canada. In Canada, there are approximately 25,000 grizzly bears occupying British Columbia, Alberta, the tundra areas of the Ungava Peninsula and the northern tip of Labrador-Quebec,[23] the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and the northern part of Manitoba.[9] In British Columbia, grizzly bears inhabit approximately 90% of their original territory. There were approximately 25,000 grizzly bears in British Columbia when the European settlers arrived.[9] However, population size has since significantly decreased due to hunting and habitat loss. In 2008, it was estimated there were 16,014 grizzly bears. Population estimates for British Columbia are based on hair-snagging, DNA-based inventories, mark-and-recapture, and a refined multiple regression model.[24] In 2003, researchers from the University of Alberta spotted a grizzly on Melville Island in the high Arctic, which is the most northerly sighting ever documented.[25][26]

The Alaskan population of 30,000 individuals is the highest population of any province/state in North America. Populations in Alaska are densest along the coast, where food supplies such as salmon are more abundant.[27] The Admiralty Island National Monument protects the densest population — 1,600 bears on a 1,600-square mile island.[28]

Continental United States[edit]

Only about 1,500 grizzlies are left in the lower 48 states of the US.[29] Of these, about 800 live in Montana.[30] About 600 more live in Wyoming, in the Yellowstone-Teton area.[31]There are an estimated 70–100 grizzly bears living in northern and eastern Idaho. Its original range included much of the Great Plains and the southwestern states, but it has been extirpated in most of those areas. Combining Canada and the United States, grizzly bears inhabit approximately half the area of their historical range.[9]

In September 2007, a hunter produced evidence of one bear in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness ecosystem, by killing a male grizzly bear there.[32] In the North Cascadesecosystem of northern Washington, grizzly bear populations are estimated to be less than 20 bears and only one sighting of a grizzly bear in the last 10 years has been recorded.[33] There has been no confirmed sighting of a grizzly in Colorado since 1979.[34]

Other provinces and the United States may use a combination of methods for population estimates. Therefore, it is difficult to say precisely what methods were used to produce total population estimates for Canada and North America, as they were likely developed from a variety of studies. The grizzly bear currently has legal protection in Mexico,European countries, some areas of Canada and in the United States. However, it is expected that repopulating its former range will be a slow process, due to a variety of reasons including the bear's slow reproductive habits and the effects of reintroducing such a large animal to areas prized for agriculture and livestock. Competition with competing predators and predation on cubs is another possible limiting factor for grizzly bear recovery, though grizzly bears also benefit from scavenged carcasses from predators as an easy food source when other food sources decline. There are currently about 55,000 wild grizzly bears total located throughout North America, most of which reside in Alaska.[9]

Longevity[edit]

The grizzly bear is, by nature, a long-living animal. Females live longer than males due to their less dangerous life, avoiding the seasonal breeding fights males engage in. The average lifespan for a male is estimated at 22 years, with that of a female being slightly longer at 26.[35] The oldest wild inland grizzly was 34 years old in Alaska; the oldest coastal bear was 39.[36] Captive grizzlies have lived as long as 44 years, but most grizzlies die in their first few years of life from predation or hunting.[37]

Hibernation[edit]

Grizzly bears hibernate for 5–7 months each year[38] except where the climate is warm, as the California grizzly did not hibernate.[2] During this time, female grizzly bears give birth to their offspring, who then consume milk from their mother and gain strength for the remainder of the hibernation period.[39] To prepare for hibernation, grizzlies must prepare a den, and consume an immense amount of food as they do not eat during hibernation. Grizzly bears do not defecate or urinate throughout the entire hibernation period. The male grizzly bear's hibernation ends in early to mid-March, while females emerge in April or early May.[40]

In preparation for winter, bears can gain approximately 180 kg (400 lb), during a period of hyperphagia, before going into hibernation.[41] The bear often waits for a substantial snowstorm before it enters its den: such behavior lessens the chances predators will find the den. The dens are typically at elevations above 1,800 m (5,900 ft) on north-facing slopes.[42] There is some debate amongst professionals as to whether grizzly bears technically hibernate: much of this debate revolves around body temperature and the ability of the bears to move around during hibernation on occasion. Grizzly bears can "partially" recycle their body wastes during this period.[43] Although inland or Rocky Mountain grizzlies spend nearly half of their life in dens, coastal grizzlies with better access to food sources spend less time in dens. In some areas where food is very plentiful year round, grizzly bears skip hibernation altogether.[44]

Reproduction[edit]

Except for females with cubs,[45] grizzlies are normally solitary, active animals, but in coastal areas, grizzlies gather around streams, lakes, rivers, and ponds during the salmon spawn. Every other year, females (sows) produce one to four young (usually two)[46] which are small and weigh only about 500 grams (1 lb) at birth. A sow is protective of her offspring and will attack if she thinks she or her cubs are threatened.

Grizzly bears have one of the lowest reproductive rates of all terrestrial mammals in North America.[47] This is due to numerous ecological factors. Grizzly bears do not reach sexual maturity until they are at least five years old.[9][48] Once mated with a male in the summer, the female delays embryo implantation until hibernation, during which miscarriage can occur if the female does not receive the proper nutrients and caloric intake.[49] On average, females produce two cubs in a litter[48] and the mother cares for the cubs for up to two years, during which the mother will not mate.[9] Once the young leave or are killed, females may not produce another litter for three or more years, depending on environmental conditions.[50] Male grizzly bears have large territories, up to 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi),[47] making finding a female scent difficult in such low population densities. Population fragmentation of grizzlies may destabilize the population from inbreeding depression. The gestation period for grizzly bears is approximately 180–250 days.

Litter size is between one and four cubs, averaging twins or triplets. Cubs are always born in the mother's winter den while she is in hibernation. Female grizzlies are fiercely protective of their cubs, being able to fend off predators as large as male bears bigger than they are in defense of the cubs.[51] Cubs feed entirely on their mother's milk until summer comes, after which they still drink milk but begin to eat solid foods. Cubs gain weight rapidly during their time with the mother — their weight will have ballooned from 4.5 to 45 kg (10 to 99 lb) in the two years spent with the mother. Mothers may see their cubs in later years but both avoid each other.[52]

Diet[edit]

Although grizzlies are of the order Carnivora and have the digestive system of carnivores, they are normally omnivores: their diets consist of both plants and animals. They have been known to prey on large mammals, when available, such as moose, elk, caribou, white-tailed deer, mule deer, bighorn sheep,bison, and even black bears; though they are more likely to take calves and injured individuals rather than healthy adults. Grizzly bears feed on fish such as salmon, trout, and bass, and those with access to a more protein-enriched diet in coastal areas potentially grow larger than inland individuals. Grizzly bears also readily scavenge food or carrion left behind by other animals.[53] Grizzly bears will also eat birds and their eggs, and gather in large numbers at fishing sites to feed on spawning salmon. They frequently prey on baby deer left in the grass, and occasionally they raid the nests of raptors such as bald eagles.[54]

Canadian or Alaskan grizzlies are larger than those that reside in the American Rocky Mountains. This is due, in part, to the richness of their diets. In Yellowstone National Park in the United States, the grizzly bear's diet consists mostly of whitebarkpine nuts, tubers, grasses, various rodents, army cutworm moths, and scavenged carcasses.[55] None of these, however, match the fat content of the salmon available in Alaska and British Columbia. With the high fat content of salmon, it is not uncommon to encounter grizzlies in Alaska weighing 540 kg (1,200 lb).[56] Grizzlies in Alaska supplement their diet of salmon and clams with sedge grass and berries. In areas where salmon are forced to leap waterfalls, grizzlies gather at the base of the falls to feed on and catch the fish. Salmon are at a disadvantage when they leap waterfalls because they cluster together at their bases and are therefore easier targets for the grizzlies.[57] Grizzly bears are well-documented catching leaping salmon in their mouths at Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska. They are also very experienced in chasing the fish around and pinning them with their claws.[58][59] At such sites such as Brooks Falls and McNeil Falls in Alaska, big male grizzlies fight regularly for the best fishing spots.[60] Grizzly bears along the coast also forage for razor clams, and frequently dig into the sand to seek them.[61] During the spring and fall, directly before and after the salmon runs, berries and grass make up the mainstay of the diets of coastal grizzlies.[62]

Inland grizzlies may eat fish too, most notably in Yellowstone grizzlies eating Yellowstone cutthroat trout.[63] The relationship with cutthroat trout and grizzlies is unique because it is the only example where Rocky Mountain grizzlies feed on spawning salmonid fish.[63] However, grizzly bears themselves and invasive lake trout threaten the survival of the trout population and there is a slight chance that the trout will be eliminated.[64]

Meat, as already described, is an important part of a grizzly's diet. Grizzly bears occasionally prey on small mammals, such as marmots, ground squirrels, lemmings, andvoles.[65] The most famous example of such predation is in Denali National Park and Preserve, where grizzlies chase, pounce on, and dig up Arctic ground squirrels to eat.[66] In some areas, grizzly bears prey on hoary marmots, overturning rocks to reach them, and in some cases preying on them when they are in hibernation.[67] Larger prey includesbison and moose, which are sometimes taken by bears in Yellowstone National Park. Because bison and moose are dangerous prey, grizzlies usually use cover to stalk them and/or pick off weak individuals or calves.[68][69] Grizzlies in Alaska also regularly prey on moose calves, which in Denali National Park may be their main source of meat. In fact, grizzly bears are such important predators of moose and elk calves in Alaska and in Yellowstone, that they may kill as many as 51 percent of elk or moose calves born that year. Grizzly bears have also been blamed in the decline of elk in Yellowstone National Park when the actual predators were thought to be gray wolves.[70][71][72][73][74] In northern Alaska, grizzlies are a significant predator of caribou, mostly taking sick or old individuals or calves.[75] Several studies show that grizzly bears may follow the caribou herds year-round in order to maintain their food supply.[76][77] In northern Alaska, grizzly bears often encounter muskox. Despite the fact that muskox do not usually occur in grizzly habitat and that they are bigger and more powerful than caribou, predation on muskox by grizzlies has been recorded.[78]

Grizzly bears along the Alaskan coast also scavenge on dead or washed up whales.[79] Usually such incidents involve only one or two grizzlies at a carcass, but up to ten large males have been seen at a time eating a dead humpback whale. Dead seals and sea lions are also consumed.

Although the diets of grizzly bears vary extensively based on seasonal and regional changes, plants make up a large portion of them, with some estimates as high as 80–90%.[80]Various berries constitute an important food source when they are available. These can include blueberries, blackberries (Rubus fruticosus), salmon berries (Rubus spectabilis), cranberries (Vaccinium oxycoccos), buffalo berries (Shepherdia argentea), soapberries (Shepherdia canadensis), and huckleberries (Vaccinium parvifolium), depending on the environment. Insects such as ladybugs, ants, and bees are eaten if they are available in large quantities. In Yellowstone National Park, grizzly bears may obtain half of their yearly caloric needs by feeding on miller moths that congregate on mountain slopes.[81] When food is abundant, grizzly bears will feed in groups. For example, many grizzly bears will visit meadows right after an avalanche or glacier slide. This is due to an influx of legumes, such as Hedysarum, which the grizzlies consume in massive amounts.[82] When food sources become scarcer, however, they separate once again.

Interspecific competition[edit]

The removal of wolves and the grizzly bear in California may have greatly reduced the abundance of the endangered San Joaquin Kit Fox.[83] With the reintroduction of gray wolves to Yellowstone, many visitors have witnessed a once common struggle between a keystone species, the grizzly bear, and its historic rival, the gray wolf. The interactions of grizzly bears with the wolves of Yellowstone have been under considerable study. Typically, the conflict will be in the defense of young or over a carcass, which is commonly an elk killed by wolves.[84] The grizzly bear uses its keen sense of smell to locate the kill. As the wolves and grizzly compete for the kill, one wolf may try to distract the bear while the others feed. The bear then may retaliate by chasing the wolves. If the wolves become aggressive with the bear, it is normally in the form of quick nips at its hind legs. Thus, the bear will sit down and use its ability to protect itself in a full circle. Rarely do interactions such as these end in death or serious injury to either animal. One carcass simply is not usually worth the risk to the wolves (if the bear has the upper hand due to strength and size) or to the bear (if the wolves are too numerous or persistent).[85] While wolves usually dominate grizzly bears during interactions at wolf dens, both grizzly and black bears have been reported killing wolves and their cubs at wolf dens even when the latter was in defense mode.[86][87]

Black bears generally stay out of grizzly territory, but grizzlies may occasionally enter black bear terrain to obtain food sources both bears enjoy, such as pine nuts, acorns, mushrooms, and berries. When a black bear sees a grizzly coming, it either turns tail and runs or climbs a tree. Black bears are not strong competition for prey because they have a more herbivorous diet. Confrontations are rare because of the differences in size, habitats, and diets of the bear species. When this happens, it is usually with the grizzly being the aggressor. The black bear will only fight when it is a smaller grizzly such as a yearling or when the black bear has no other choice but to defend itself. There is at least one confirmed observation of a grizzly bear digging out, killing and eating a black bear when the latter was in hibernation.[88]

The segregation of black bear and grizzly bear populations is possibly due to competitive exclusion. In certain areas, grizzly bears outcompete black bears for the same resources.[89] For example, many Pacific coastal islands off British Columbia and Alaska support either the black bear or the grizzly, but rarely both.[90] In regions where both species coexist, they are divided by landscape gradients such as age of forest, elevation and openness of land. Grizzly bears tend to favor old forests with high productivity, higher elevations and more open habitats compared with black bears.[89]

The relationship between grizzly bears and other predators is mostly one-sided; grizzly bears will approach feeding predators to steal their kill. In general, the other species will leave the carcasses for the bear to avoid competition or predation. Any parts of the carcass left uneaten are scavenged by smaller animals.[91] Cougars generally give the bears a wide berth. Grizzlies have less competition with cougars than with other predators, such as coyotes, wolves, and other bears. When a grizzly descends on a cougar feeding on its kill, the cougar usually gives way to the bear. When a cougar does stand its ground, it will use its superior agility and its claws to harass the bear, yet stay out of its reach until one of them gives up. Grizzly bears occasionally kill cougars in disputes over kills.[92] There have been several accounts, primarily from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of cougars and grizzly bears killing each other in fights to the death.[93]

Coyotes, foxes, and wolverines are generally regarded as pests to the grizzlies rather than competition, though they may compete for smaller prey, such as ground squirrels and rabbits. All three will try to scavenge whatever they can from the bears. Wolverines are aggressive enough to occasionally persist until the bear finishes eating, leaving more than normal scraps for the smaller animal.[91] Packs of coyotes have also displaced grizzly bears in disputes over kills.[94]

Ecological role[edit]

The grizzly bear has several relationships with its ecosystem. One such relationship is a mutualistic relationship with fleshy-fruit bearing plants. After the grizzly consumes the fruit, the seeds are excreted and thereby dispersed in a germinable condition. Some studies have shown germination success is indeed increased as a result of seeds being deposited along with nutrients in feces.[95] This makes grizzly bears important seed distributors in their habitats.[96]

While foraging for tree roots, plant bulbs, or ground squirrels, bears stir up the soil. This process not only helps grizzlies access their food, but also increases species richness in alpine ecosystems.[97] An area that contains both bear digs and undisturbed land has greater plant diversity than an area that contains just undisturbed land.[97] Along with increasing species richness, soil disturbance causes nitrogen to be dug up from lower soil layers, and makes nitrogen more readily available in the environment.[98] An area that has been dug by the grizzly bear has significantly more nitrogen than an undisturbed area.

Nitrogen cycling is not only facilitated by grizzlies digging for food, it is also accomplished via their habit of carrying salmon carcasses into surrounding forests.[99] It has been found that spruce tree (Picea glauca) foliage within 500 m (1,600 ft) of the stream where the salmon have been obtained contains nitrogen originating from salmon on which the bears preyed.[100] These nitrogen influxes to the forest are directly related to the presence of grizzly bears and salmon.[101]

Grizzlies directly regulate prey populations and also help prevent overgrazing in forests by controlling the populations of other species in the food chain.[102] An experiment inGrand Teton National Park in Wyoming in the United States showed removal of wolves and grizzly bears caused populations of their herbivorous prey to increase.[103] This, in turn, changed the structure and density of plants in the area, which decreased the population sizes of migratory birds.[103] This provides evidence grizzly bears represent a keystone predator, having a major influence on the entire ecosystem they inhabit.[102]

When grizzly bears fish for salmon along the coasts of Alaska and British Columbia, they often only eat the skin, brain and roe of the fish. In doing so, they provide a food source for gulls, ravens, and foxes, all or which eat salmon as well; this benefits both the bear and the smaller predators.[104]

Conflicts with humans[edit]

Grizzlies are considered by experts to be more aggressive than black bears when defending themselves and their offspring.[105]Aggressive behavior in grizzly bears is favored by numerous selection variables. Unlike the smaller black bears, adult grizzlies don't climb trees well, so they respond to danger by standing their ground and warding off their attackers. Increased aggressiveness also assists female grizzlies in better ensuring the survival of their young to reproductive age.[106] Mothers defending their cubs are the most prone to attacking, being responsible for 70% of fatal injuries to humans.[107]

Grizzly bears normally avoid contact with people. In spite of their obvious physical advantages and many opportunities, they almost never view humans as prey; bears rarely actively hunt humans.[108] Most grizzly bear attacks result from a bear that has been surprised at very close range, especially if it has a supply of food to protect, or female grizzlies protecting their offspring. In such situations, property may be damaged and the bear may physically harm the person.[109] If a bear kills a human in a national park likeYellowstone, the park superintendent will evaluate if the bear has to be killed, to prevent the bear killing humans again in the future.[110]

Exacerbating this is the fact that intensive human use of grizzly habitat coincides with the seasonal movement of grizzly bears.[109] An example of this spatiotemporal intersection occurs during the fall season: grizzly bears congregate near streams to feed on salmon when anglers are also intensively using the river.

Increased human–bear interaction has created "problem bears", which are bears that have become adapted to human activities or habitat.[111]Aversive conditioning, a method involving using deterrents such as rubber bullets, foul-tasting chemicals, or acoustic deterrent devices to teach bears to associate humans with negative experiences, is ineffectual when bears have already learned to positively associate humans with food.[112] Such bears are translocated or killed because they pose a threat to humans. The B.C. government kills approximately 50 problem bears each year[112] and overall spends more than one million dollars annually to address bear complaints, relocate bears and kill them.[112]

Bear awareness programs have been developed by many towns in British Columbia, Canada, to help prevent conflicts with both black and grizzly bears. The main premise of these programs is to teach humans to manage foods that attract bears. Keeping garbage securely stored, harvesting fruit when ripe, securing livestock behind electric fences, and storing pet food indoors are all measures promoted by bear aware programs. The fact that grizzly bears are less numerous and even protected in some areas, means that preventing conflict with grizzlies is especially important. Revelstoke, British Columbia is a community that demonstrates the success of this approach. In the ten years preceding the development of a community education program in Revelstoke, 16 grizzlies were destroyed and a further 107 were relocated away from the town. An education program run by Revelstoke Bear Aware was put in place in 1996. Since the program began just 4 grizzlies have been destroyed and 5 have been relocated.[113]

For back-country campers, hanging food between trees at a height unreachable to bears is a common procedure, although some grizzlies can climb and reach hanging food in other ways. An alternative to hanging food is to use a bear canister.[114]

Traveling in groups of six or more can significantly reduce the chance of bear-related injuries while hiking in bear country.[115]

Grizzly bears are especially dangerous because of the strength of their bite, which has been measured at over 8 megapascals (1160 psi). It has been estimated that a bite from a grizzly could crush a bowling ball.[116]

Protection[edit]

The grizzly bear is listed as threatened in the contiguous United States and endangered in parts of Canada. In May 2002, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the Prairie population (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba range) of grizzly bears as extirpated in Canada.[117]As of 2002, grizzly bears were listed as special concern under the COSEWIC registry[118] and considered threatened under the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[119]

Within the United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concentrates its effort to restore grizzly bears in six recovery areas. These are Northern Continental Divide (Montana), Yellowstone (Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho), Cabinet-Yaak (Montana and Idaho), Selway-Bitterroot (Montana and Idaho), Selkirk (Idaho and Washington), and North Cascades (Washington). The grizzly population in these areas is estimated at 750 in the Northern Continental Divide, 550 in Yellowstone, 40 in the Yaak portion of the Cabinet-Yaak, and 15 in the Cabinet portion (in northwestern Montana), 105 in Selkirk region of Idaho, 10–20 in the North Cascades, and none currently in Selway-Bitterroots, although there have been sightings.[120] These are estimates because bears move in and out of these areas, and it is therefore impossible to conduct a precise count. In the recovery areas that adjoin Canada, bears also move back and forth across the international boundary.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service claims the Cabinet-Yaak and Selkirk areas are linked through British Columbia, a claim that is disputed.[121] U.S. and Canadian national parks, such as Banff National Park, Yellowstone and Grand Teton, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park are subject to laws and regulations designed to protect the bears.

On 9 January 2006, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to remove Yellowstone grizzlies from the list of threatened and protected species.[122] In March 2007, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service "de-listed" the population,[123] effectively removing Endangered Species Act protections for grizzlies in the Yellowstone National Park area. Several environmental organizations, including the NRDC, brought a lawsuit against the federal government to relist the grizzly bear. On 22 September 2009, U.S. District Judge Donald W. Molloy reinstated protection due to the decline of whitebark pine tree, whose nuts are an important source of food for the bears.[124] In 1996 the International Union for Conservation of Nature moved the grizzly bear to the lower risk "Least Concern" status on the IUCN Red List.[125][126]

Farther north, in Alberta, Canada, intense DNA hair-snagging studies in 2000 showed the grizzly population to be increasing faster than what it was formerly believed to be, and Alberta Sustainable Resource Development calculated a population of 841 bears.[127] In 2002, the Endangered Species Conservation Committee recommended that the Alberta grizzly bear population be designated as threatened due to recent estimates of grizzly bear mortality rates that indicated the population was in decline. A recovery plan released by the provincial government in March 2008 indicated the grizzly population is lower than previously believed.[128] In 2010, the provincial government formally listed its population of about 700 grizzlies as "Threatened".[129]

Environment Canada consider the grizzly bear to a "special concern" species, as it is particularly sensitive to human activities and natural threats. In Alberta and British Columbia, the species is considered to be at risk.[130] In 2008, it was estimated there were 16,014 grizzly bears in the British Columbia population, which was lower than previously estimated due to refinements in the population model.[131]

Conservation efforts[edit]

Conservation efforts have become an increasingly vital investment over recent decades, as population numbers have dramatically declined. Establishment of parks and protected areas are one of the main focuses currently being tackled to help reestablish the low grizzly bear population in British Columbia. One example of these efforts is the Khutzeymateen Grizzly Bear Sanctuary located along the north coast of British Columbia; at 44,300 hectares (109,000 acres) in size, it is composed of key habitat for this threatened species. Regulations such as limited public access, as well as a strict no hunting policy, have enabled this location to be a safe haven for local grizzlies in the area.[134] When choosing the location of a park focused on grizzly bear conservation, factors such as habitat quality and connectivity to other habitat patches are considered.

The Refuge for Endangered Wildlife located on Grouse Mountain in Vancouver is an example of a different type of conservation effort for the diminishing grizzly bear population. The refuge is a five-acre terrain which has functioned as a home for two orphaned grizzly bears since 2001.[135] The purpose of this refuge is to provide awareness and education to the public about grizzly bears, as well as providing an area for research and observation of this secluded species.

Another factor currently being taken into consideration when designing conservation plans for future generations are anthropogenic barriers in the form of urban development and roads. These elements are acting as obstacles, causing fragmentation of the remaining grizzly bear population habitat and prevention of gene flow between subpopulations (for example, Banff National Park). This, in turn, is creating a decline in genetic diversity, and therefore the overall fitness of the general population is lowered.[136] In light of these issues, conservation plans often include migration corridors by way of long strips of "park forest" to connect less developed areas, or by way of tunnels and overpasses over busy roads.[137] Using GPS collar tracking, scientists can study whether or not these efforts are actually making a positive contribution towards resolving the problem.[138] To date, most corridors are found to be infrequently used, and thus genetic isolation is currently occurring, which can result in inbreeding and therefore an increased frequency of deleterious genes through genetic drift.[139] Current data suggest female grizzly bears are disproportionately less likely than males to use these corridors, which can prevent mate access and decrease the number of offspring.

In the United States, national efforts have been made since 1982 for the recovery plan of grizzly bears.[140] A lot of the efforts made have been through different organizations efforts to educate the public on grizzly bear safety, habits of grizzly bears and different ways to reduce human-bear conflict. The Interagency Grizzly Bear Recovery Committee is one of many organizations committed to the recovery of grizzly bears in the lower 48 states.[141] There are five recovery zones for grizzly bears in the lower 48 states including the North Cascades ecosystem in Washington state.[142] The National Park Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife initiated the process of an environmental impact statement that started in the fall of 2014 to begin the recovery process of grizzly bears to the North Cascades region.[142] A final plan and environmental impact statement is expected to be released in the spring of 2017 and a record of decision in the summer of 2017.[142]

Bear-watching[edit]

In the past 20 years in Alaska, ecotourism has boomed. While many people come to Alaska to bear-hunt, the majority come to watch the bears and observe their habits. Some of the best bear viewing in the world occurs on coastal areas of the Alaska Peninsula, including in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, Katmai National Park and Preserve, and the McNeil River State Game Sanctuary and Refuge. Here bears gather in large numbers to feast on concentrated food sources, including sedges in the salt marshes, clams in the nearby tidal flats, salmon in the estuary streams, and berries on the neighboring hillsides.

Katmai National Park and Preserve is one of the best spots to view brown bears. The bear population in Katmai is estimated at a healthy 2100.[143] The park is located on the Alaskan Peninsula about 480 km (300 mi) southwest of the city of Anchorage. At Brooks Camp, a famous site exists where grizzlies can be seen catching salmon from atop a platform—you can even view this online from a cam.[144] In coastal areas of the park, such as Hallo Bay, Geographic Harbor, Swikshak Lagoon, American Creek, Big River, Kamishak River, Savonoski River, Moraine Creek, Funnel Creek, Battle Creek, Nantuk Creek,[145] Kukak Bay, and Kaflia Bay you can often watch bears fishing alongside wolves, eagles, and river otters. Coastal areas host the highest population densities year round because there is a larger viariety of food sources available, but Brooks Camp hosts the highest population (100 bears).[146]

The McNeil River State Game Sanctuary and Refuge, on the McNeil River, is home to the greatest concentration of brown bears in the world. An estimated 144 individual bears have been identified at the falls in a single summer with as many as 74 at one time;[147] 60 or more bears at the falls is a frequent sight, and it is not uncommon to see 100 bears at the falls throughout a single day.[148] The McNeil River State Game Refuge, containing Chenik Lake and a smaller number of grizzly bears, has been closed to grizzly hunting since 1995.[149] All of the Katmai-McNeil area is closed to hunting except for Katmai National Preserve, where regulated legal hunting takes place.[150] In all, the Katmai-McNeil area has an estimated 2500 grizzly bears.[151]

Admiralty Island, in southeast Alaska, was known to early natives as Xootsnoowú, meaning "fortress of bears," and is home to the densest grizzly population in North America. An estimated 1600 grizzlies live on the island, which itself is only 140 km (90 mi) long.[152] The best place to view grizzly bears in the island is probably Pack Creek, in the Stan Price State Wildlife Sanctuary. 20 to 30 grizzlies can be observed at the creek at one time and like Brooks Camp, visitors can watch bears from an above platform.[153] Kodiak Island, hence its name, is another good place to view bears. An estimated 3500 Kodiak grizzly bears inhabit the island, 2300 of these in the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge.[154][155] TheO'Malley River is considered the best place on Kodiak Island to view grizzly bears.[156]

**Barbed wire

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire, less often bob wire[1][2] or, in the southeastern United States, bobbed wire,[3] is a type of steelfencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strand(s). It is used to construct inexpensive fencesand is used atop walls surrounding secured property. It is also a major feature of the fortifications in trench warfare (as a wire obstacle).

A person or animal trying to pass through or over barbed wire will suffer discomfort and possibly injury. Barbed wire fencing requires only fence posts, wire, and fixing devices such as staples. It is simple to construct and quick to erect, even by an unskilled person.

A person or animal trying to pass through or over barbed wire will suffer discomfort and possibly injury. Barbed wire fencing requires only fence posts, wire, and fixing devices such as staples. It is simple to construct and quick to erect, even by an unskilled person.

The first patent in the United States for barbed wire was issued in 1867 to Lucien B. Smith of Kent, Ohio, who is regarded as the inventor.[4][5] Joseph F. Glidden of DeKalb, Illinois, received a patent for the modern invention in 1874 after he made his own modifications to previous versions.

Barbed wire was the first wire technology capable of restraining cattle. Wire fences were cheaper and easier to erect than their alternatives. (One such alternative was Osage orange, a thorny bush which was time-consuming to transplant and grow. The Osage orange later became a supplier of the wood used in making barb wire fence posts.[6]) When wire fences became widely available in the United States in the late 19th century, they made it affordable to fence much larger areas than before. They made intensive animal husbandry practical on a much larger scale.

An example of the costs of fencing with lumber immediately prior to the invention of barbed wire can be found with the first farmers in theFresno, California area, who spent nearly $4000 (over $75,000 in present-day dollars) to have wood for fencing delivered and erected to protect 2500 acres of wheat crop from free-ranging livestock in 1872.[7]

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

Before 1865[edit]

Englishman Richard Newton brought barbed wire to the Argentine pampas in 1845.[8]

Fencing consisting of flat and thin wire was first proposed in France, by Leonce Eugene Grassin-Baledans in 1860. His design consisted of bristling points, creating a fence that was painful to cross. In April 1865 Louis François Janin proposed a double wire with diamond-shaped metal barbs; he was granted a patent. Michael Kelly from New York had a similar idea, and proposed that the fencing should be used specifically for deterring animals.[9]

More patents followed, and in 1867 alone there were six patents issued for barbed wire. Only two of them addressed livestock deterrence, one of which was from American Lucien B. Smith of Ohio.[10] Before 1870, westward movement in the USA was largely across the plains with little or no settlement occurring. After the American Civil War the plains were extensively settled, consolidating America's dominance over them.[11]

Ranchers moved out on the plains, and needed to fence their land in against encroaching farmers and other ranchers. The railroads throughout the growing West needed to keep livestock off their tracks, and farmers needed to keep stray cattle from trampling their crops.[12] Traditional fence materials used in the Eastern U.S., like wood and stone, were expensive to use in the large open spaces of the plains, and hedging was not reliable in the rocky, clay-based and rain-starved dusty soils. A cost-effective alternative was needed to make cattle operations profitable.[13]

The 1873 meeting and initial development[edit]

The "Big Four" in barbed wire were Joseph Glidden, Jacob Haish, Charles Francis Washburn, and Isaac L. Ellwood.[14] Glidden, a farmer in 1873 and the first of the "Big Four," is often credited for designing a successful sturdy barbed wire product, but he let others popularize it for him. Glidden's idea came from a display at a fair in DeKalb, Illinois in 1873, by Henry B. Rose. Rose had patented "The Wooden Strip with Metallic Points" in May 1873.[15]

This was simply a wooden block with wire protrusions designed to keep cows from breaching the fence. That day, Glidden was accompanied by two other men, Isaac L. Ellwood, a hardware dealer and Jacob Haish, a lumber merchant. Like Glidden, they both wanted to create a more durable wire fence with fixed barbs. Glidden experimented with a grindstone to twist two wires together to hold the barbs on the wire in place. They were created from experiments with a coffee mill from his home.[15]

Later Glidden was joined by Ellwood who knew his design could not compete with Glidden's for which he applied for a patent in October 1873.[16] Meanwhile, Haish, who had already secured several patents for barbed wire design, applied over a week before Glidden for a patent on his third type of wire, the S barb, and accused Glidden of interference, deferring Glidden's approval for his patented wire nicknamed "The Winner" until November 24, 1874.[17]

Barbed wire production greatly increased with Glidden and Ellwood’s establishment of the Barb Fence Company in DeKalb following the success of "The Winner". The company's success attracted the attention of Charles Francis Washburn, Vice President of Washburn & Moen Manufacturing Company, an important producer of plain wire in the Eastern U.S. Washburn visited De Kalb and convinced Glidden to sell his stake in the Barb Wire Fence Company, while Ellwood stayed in DeKalb and renamed the company I.L Ellwood & Company of DeKalb.[18]

Promotion and consolidation[edit]

In the late 1870s, John Warne Gates of Illinois began to promote barbed wire, now a proven product, in the lucrative markets of Texas. At first, Texans were hesitant, as they feared that cattle might be harmed, or that the North was somehow trying to make profits from the South. There was also conflict between the farmers who wanted fencing and the ranchers who were losing the open range.[12]

Demonstrations by Gates in San Antonio in 1876 showed that the wire could keep cattle contained, and sales then increased dramatically. Gates eventually parted company with Ellwood and became a barbed wire baron in his own right. Throughout the height of barbed wire sales in the late 19th century, Washburn, Ellwood, Gates, and Haish competed with one another, but Ellwood and Gates eventually joined forces again to create the American Steel and Wire Company, later acquired by The U.S. Steel Corporation.[19]

Between 1873 and 1899 there were as many as 150 companies manufacturing barbed wire to cash in on the demand in the West: investors were aware that the business did not require much capital and it was considered that almost anyone with enough determination could make a profit from manufacture of a new wire design.[20] There was then a sharp decline in the number of manufacturing firms, as many were consolidated into larger companies, notably the American Steel and Wire Company, formed by the merging of Gates's and Washburn's and Ellwood's industries.

Smaller companies were wiped out because of economies of scale and the smaller pool of consumers available to them, compared to the larger corporations. The American Steel and Wire Company established in 1899 employed vertical integration: it controlled all aspects of production from producing the steel rods to making many different wire and nail products from the same steel; although later part of U.S. Steel, the production of barbed wire would still be a major source of revenue

Another inventor, William Edenborn, a German immigrant who later settled in Winn Parish, Louisiana, patented a machine which simplified the making of barbed wire and cut the unit price of production from seventeen to three cents per pound. His particular wire is the "humane" version that did not harm cattle. The original wire was sharp-teethed and contributed to western range wars. Edenborn's company in time supplied 75 percent of the barbed wire in the United States. A wire nail machine that he also patented reduced the price of wire nails from eight to two cents per pound.[21][22]

Historical uses[edit]

In the American West[edit]

Barbed wire played an important role in the protection of range rights in the Western U.S. Although some ranchers put notices in newspapers claiming land areas, and joined stockgrowers associations to help enforce their claims, livestock continued to cross range boundaries. Fences of smooth wire did not hold stock well, and hedges were difficult to grow and maintain. Barbed wire's introduction in the West in the 1870s dramatically reduced the cost of enclosing land.[23]

One fan wrote the inventor Joseph Glidden:

- it takes no room, exhausts no soil, shades no vegetation, is proof against high winds, makes no snowdrifts, and is both durable and cheap.[24]

Barbed wire also emerged as a major source of conflict with the so-called “Big Die Up” incident in the 1880s. This conflict occurred because of the instinctual migrations of cattle away from the blizzard conditions of the Northern Plains to the warmer and plentiful Southern Plains, but by the early 1880s this area was already divided and claimed by ranchers. The ranchers in place, especially in the Texas Panhandle, knew that their holdings could not support the grazing of additional cattle, so the only alternative was to block the migrations with barb wire fencing.[25]

Many of the herds were decimated in the winter of 1885, with some losing as many as three-quarters of all animals when they could not find a way around the fence. Later other smaller scale cattlemen, especially in central Texas, opposed the closing of the open range, and began cutting fences to allow cattle to pass through to find grazing land. In this transition zone between the agricultural regions to the south and the rangeland to the north, conflict erupted, with vigilantes joining the scene causing chaos and even death. The fence cutters war came to an end with the passage of a Texas law in 1884 that stated among other provisions that fence cutting was a felony; and other states followed, although conflicts still occurred through the opening years of the 20th century.[26] A federal law passed in 1885 forbade stretching such fences across the public domain.[23]

Barbed wire is often cited by historians as the invention that truly tamed the West. Herding large numbers of cattle on open terrain required significant manpower just to catch strays, but with an inexpensive method to divide, sub-divide and allocate parcels of land to control the movement of cattle, the need for a vast labor force became unnecessary. By the beginning of the 20th century the need for significant numbers of cowboys was not necessary.[27]

In war[edit]

Barbed wire was used for the first time in the Spanish–American War during the siege of Santiago by the Spanish defenders. Less well known is its extensive usage in the Russo-Japanese War.

More significantly, barbed wire was used extensively by all participating combatants in World War I to prevent movement, with deadly consequences. Barbed wire entanglements were placed in front of trenches to prevent direct charges on men below, increasingly leading to greater use of more advanced weapons such as high powered machine guns and grenades. A feature of these entanglements was that the barbs were much closer together, often forming a continuous sequence.[28]

Barbed wire could be exposed to heavy bombardments because it could be easily replaced, and its structure included so much open space that machine guns rarely destroyed enough of it to defeat its purpose. However barbed wire was defeated by the tank in 1916, as shown by the Allied breakthrough at Amiens through German lines on August 8, 1918.[29]

In concentration camps[edit]

In 1899 barbed wire was also extensively used in the Boer War, where it played a strategic role bringing spaces under control, at military outposts as well as to hold the captured Boer population in concentration camps.

In the 1930s and 1940s Europe the Nazis used barbed wire in concentration camp architecture, where it usually surrounded the camp and was electrified to prevent escape. Barbed wire served the purpose of keeping prisoners contained.

Infirmaries in extermination camps like Auschwitz where prisoners were gassed or experimented on were often separated from other areas by electrified wire and were often braided with branches to prevent outsiders from knowing what was concealed behind their walls.[30]

In the Southwest United States[edit]

John Warne Gates demonstrated barbed wire for Washburn and Moen in Military Plaza, San Antonio, Texas in 1876. The demonstration showing cattle restrained by the new kind of fencing was followed immediately by invitations to the Menger Hotel to place orders. Gates subsequently had a falling out with Washburn and Moen and Isaac Ellwood. He moved to St. Louis and founded the Southern Wire Company, which became the largest manufacturer of unlicensed or "bootleg" barbed wire.

An 1880 US District Court decision upheld the validity of the Glidden patent, effectively establishing a monopoly. This decision was affirmed by the US Supreme Court in 1892. In 1898 Gates took control of Washburn and Moen, and created the American Steel and Wire monopoly, which became a part of the United States Steel Corporation.

This led to disputes known as the range wars between open range ranchers and farmers in the late 19th century. These were similar to the disputes which resulted from enclosure laws in England in the early 18th century. These disputes were decisively settled in favor of the farmers, and heavy penalties were instituted for cutting a barbed wire fence. Within 2 years, nearly all of the open range had been fenced in under private ownership. For this reason, some historians have dated the end of the Old West era of American history to the invention and subsequent proliferation of barbed wire.

Agricultural fencing[edit]

Barbed wire fences remain the standard fencing technology for enclosing cattle in most regions of the US, but not all countries. The wire is aligned under tension between heavy, braced, fence posts (strainer posts) and then held at the correct height by being attached to wooden or steel fence posts, and/or with battens in between.

The gaps between posts vary depending on type and terrain. On short fences in hilly country, steel posts may be placed every 3 yards (2.7 m), while in flat terrain with long spans and relatively few stock they may be spaced up to 30 to 50 yards (46 m). Wooden posts are normally spaced at 11 yards (10 m) (2 rods) on all terrain, with 4 or 5 battens in between. However, many farmers place posts 2 yards (1.8 m) apart as battens can bend, causing wires to close in on one another.

Barbed wire for agricultural fencing is typically available in two varieties: soft or mild-steel wire and high-tensile. Both types are galvanized for longevity. High-tensile wire is made with thinner but higher-strength steel. Its greater strength makes fences longer lasting because it resists stretching and loosening better, coping with expansion and contraction caused by heat and animal pressure by stretching and relaxing within wider elastic limits. It also supports longer spans, but because of its elastic (springy) nature it is harder to handle and somewhat dangerous for inexperienced fencers. Soft wire is much easier to work but is less durable and only suitable for short spans such as repairs and gates, where it is less likely to tangle.

In high soil-fertility areas where dairy cattle are used in great numbers 5- or 7-wire fences are common as the main boundary and internal dividing fences. On sheep farms 7-wire fences are common with the second (from bottom) to fifth wire being plain wire. In New Zealand wire fences must provide passage for dogs since they are the main means of controlling and driving animals on farms.

Gates[edit]

As with any fence, barbed wire fences require gates to allow the passage of persons, vehicles and farm implements. Gates vary in width from 12 feet (3.7 m) to allow the passage of vehicles and tractors, to 40 feet (12 m) on farm land to pass combines and swathers.

One style of gate is called the Hampshire gate in the UK, a New Zealand gate in some areas, and often simply a "gate" elsewhere. Made of wire with posts attached at both ends and in the middle, it is permanently wired on one side and attaches to a gate post with wire loops on the other. Most designs can be opened by hand, though some gates that are frequently opened and closed may have a lever attached to assist in bringing the upper wire loop over the gate post

Gates for cattle tend to have 4 wires when along a three wire fence, as cattle tend to put more stress on gates, particularly on corner gates. The fence on each side of the gated ends with two corner posts braced or unbraced depending on the size of the post. An unpounded post (often an old broken post) is held to one corner post with wire rings which act as hinges. On the other end a full length post, the tractor post, is placed with the pointed end upwards with a ring on the bottom stapled to the other corner post, the latch post, and on top a ring is stapled to the tractor post, the post is tied with a Stockgrower's Lash or one of numerous other opening bindings. Wires are then tied around the post at one end then run to the other end where they are stretched by hand or with a stretcher, before posts are stapled on every 4 feet (1.2 m), often this type of gate is called a portagee fence or a portagee gate in various ranching communities of coastal Central California.

Most gates can be opened by push post. The chain is then wrapped around the tractor post and pulled onto the nail, stronger people can pull the gate tighter but anyone can jar off the chain to open the gate.

Human-proof fencing[edit]

Most barbed wire fences, while sufficient to discourage cattle, are passable by humans who can simply climb over the fence, or through the fence by stretching the gaps between the wires using non-barbed sections of the wire as hand holds. To prevent humans crossing, many prisons and other high-security installations construct fences with razor wire, a variant which instead of occasional barbs features near-continuous cutting surfaces sufficient to injure unprotected persons who climb on it. However, it has been banned in the United Kingdom; and any person(s) erecting anti-human wire fences can be prosecuted under applicable laws.[citation needed]

A commonly seen alternative is the placement of a few strands of barbed wire at the top of a chain link fence. The limited mobility of someone climbing a fence makes passing conventional barbed wire more difficult. On some chain link fences these strands are attached to a bracket tilted 45 degrees towards the intruder, further increasing the difficulty.

Barbed wire began to be widely used as an implement of war during World War I. Wire was placed either to impede or halt the passage of soldiers, or to channel them into narrow defiles in which small arms, particularly machine guns, and indirect fire could be used with greater effect as they attempted to pass. Artillery bombardments on the Western Front became increasingly aimed at cutting the barbed wire that was a major component of trench warfare, particularly once new "wire-cutting" fuzes were introduced midway through the war.

As the war progressed the wire was used in shorter lengths that were easier to transport and more difficult to cut with artillery. Other inventions were also a result of the war, such as the screw picket, which enabled construction of wire obstacles to be done at night in No Man's Land without the necessity of hammering stakes into the ground and drawing attention from the enemy.

During the Soviet-Afghan War, the accommodation of Afghan refugees into Pakistan was controlled in Pakistan's largest province, Balochistan, under General Rahimuddin Khan, by making the refugees stay for controlled durations in barbed wire camps (see Controlling Soviet-Afghan War Refugees).

The frequent use of barbed wire on prison walls, around concentration camps, and the like, has made it symbolic of oppression and denial of freedom in general. For example, in Germany the totality of the complex German Democratic Republic border regime is commonly referred to with the short phrase "Mauer und Stacheldraht" (that is, "wall and barbed wire"), and Amnesty International has a barbed wire in their symbol. Recently, Britain and France have begun restricting the use of barbed wire due to the risk of injury it poses to trespassers.[31]

Injuries caused by barbed wire[edit]

Movement against barbed wire can result in moderate to severe injuries to the skin and, depending on body area and barbed wire configuration, possibly to the underlying tissue. Humans can manage not to injure themselves excessively when dealing with barbed wire as long as they are cautious. Restriction of movement, appropriate clothing, and slow movement when close to barbed wire aid in reducing injury.

Infantrymen are often trained and inured to the injuries caused by barbed wire. Several soldiers can lie across the wire to form a bridge for the rest of the formation to pass over; often any injury thus incurred is due to the tread of those passing over and not to the wire itself.[citation needed]

Injuries caused by barbed wire are typically seen in horses, bats, or birds. Horses panic easily, and once caught in barbed wire, large patches of skin may be torn off. At best, such injuries may heal, but they may cause disability or death (particularly due to infection). Birds or bats may not be able to perceive thin strands of barbed wire and suffer injuries.

For this reason horse fences may have rubber bands nailed parallel to the wires. More than 60 different species of wildlife have been reported in Australia as victims of entanglement on barbed wire fences, and the wildlife friendly fencing project is beginning to address this problem.[citation needed] Grazing animals with slow movements that will back off at the first notion of pain (e.g., sheep and cows) will not generally suffer the severe injuries often seen in other animals.

Barbed wire has been reported as a tool for human torture.[32] It is also frequently used as a weapon in hardcore professional wrestling matches, often as a covering for another type of weapon—Mick Foley was infamous for using a baseball bat wrapped in barbed wire—and infrequently as a covering of or substitute for the ring ropes.

Installation of barbed wire[edit]

The most important and most time-consuming part of a barbed wire fence is constructing the corner post and the bracing assembly. A barbed wire fence is under tremendous tension, often up to half a ton, and so the corner post's sole function is to resist the tension of the fence spans connected to it. The bracing keeps the corner post vertical and prevents slack from developing in the fence.

Brace posts are placed in-line about 8 feet (2.4 m) from the corner post. A horizontal compression brace connects the top of the two posts, and a diagonal wire connects the top of the brace post to the bottom of the corner post. This diagonal wire prevents the brace post from leaning, which in turn allows the horizontal brace to prevent the corner post from leaning into the brace post. A second set of brace posts (forming a double brace) is used whenever the barbed wire span exceeds 200 feet (61 m).

When the barbed wire span exceeds 650 ft (200 m), a braced line assembly is added in-line. This has the function of a corner post and brace assembly but handles tension from opposite sides. It uses diagonal brace wire that connects the tops to the bottoms of all adjacent posts.

Line posts are installed along the span of the fence at intervals of 8 to 50 ft (2.4 to 15.2 m). An interval of 16 ft (4.9 m) is most common. Heavy livestock and crowded pasture demands the smaller spacing. The sole function of a line post is not to take up slack but to keep the barbed wire strands spaced equally and off the ground.

Once these posts and bracing have been erected, the wire is wrapped around one corner post, held with a hitch (a timber hitch works well for this) often using a staple to hold the height and then reeled out along the span of the fence replacing the role every 400 m. It is then wrapped around the opposite corner post, pulled tightly with wire stretchers, and sometimes nailed with more fence staples, although this may make readjustment of tension or replacement of the wire more difficult. Then it is attached to all of the line posts with fencing staples driven in partially to allow stretching of the wire.

There are several ways to anchor the wire to a corner post:

- Hand-knotting. The wire is wrapped around the corner post and knotted by hand. This is the most common method of attaching wire to a corner post. A timber hitch works well as it stays better with wire than with rope.

- Crimp sleeves. The wire is wrapped around the corner post and bound to the incoming wire using metal sleeves which are crimped using lock cutters. This method should be avoided because while sleeves can work well on repairs in the middle of the fence where there is not enough wire for hand knotting, they tend to slip when under tension.

- Wire vise. The wire is passed through a hole drilled into the corner post and is anchored on the far side.

- Wire wrap. The wire is wrapped around the corner post and wrapped onto a special, gritted helical wire which also wraps around the incoming wire, with friction holding it in place.

Barbed wire for agriculture use is typically double-strand 12½-gauge, zinc-coated (galvanized) steel and comes in rolls of 1,320 ft (400 m) length. Barbed wire is usually placed on the inner (pasture) side of the posts. Where a fence runs between two pastures livestock could be with the wire on the outside or on both sides of the fence.

Galvanized wire is classified into three categories; Classes I, II, and III. Class I has the thinnest coating and the shortest life expectancy. A wire with Class I coating will start showing general rusting in 8 to 10 years, while the same wire with Class III coating will show rust in 15 to 20 years. Aluminum-coated wire is occasionally used, and yields a longer life.

Corner posts are 6 to 8 inches (15 to 20 cm) in diameter or larger, and a minimum 8 feet (2.4 m) in length may consist of treated wood or from durable on-site trees such as osage orange, black locust, red cedar, or red mulberry, also railroad ties, telephone, and power poles are salvaged to be used as corner posts (poles and railroad ties were often treated with chemicals determined to be an environmental hazard and cannot be reused in some jurisdictions). In Canada spruce posts are sold for this purpose. Posts are 4 inches (10 cm) in diameter driven at least 4 feet (1.2 m) and may be anchored in a concrete base 20 inches (51 cm) square and 42 inches (110 cm) deep. Iron posts, if used, are a minimum 2.5 inches (64 mm) in diameter. Bracing wire is typically smooth 9-gauge. Line posts are set to a depth of about 30 inches (76 cm). Conversely, steel posts are not as stiff as wood, and wires are fastened with slips along fixed teeth, which means variations in driving height affect wire spacing.

During the First World War, screw pickets were used for the installation of wire obstacles; these were metal rods with eyelets for holding strands of wire, and a corkscrew-like end that could literally be screwed into the ground rather than hammered, so that wiring parties could work at night near enemy soldiers and not reveal their position by the sound of hammers.