This article is about the black scholar. For other people with a similar name, see

William DuBois.

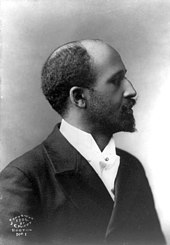

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

|---|

W. E. B. Du Bois in 1918

|

| Born | William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

February 23, 1868

Great Barrington, Massachusetts,United States |

|---|

| Died | August 27, 1963 (aged 95)

Accra, Ghana |

|---|

| Residence | Atlanta, Georgia

New York City, New York |

|---|

| Fields | Civil rights, sociology, history |

|---|

| Institutions | Atlanta University, NAACP |

|---|

| Alma mater |

|

|---|

| Known for |

|

|---|

| Influences | Alexander Crummell

William James |

|---|

| Notable awards | Spingarn Medal (1920)

Lenin Peace Prize (1959) |

|---|

| Spouse | Nina Gomer Du Bois

Shirley Graham Du Bois |

|---|

| Signature

|

William Edward Burghardt "

W. E. B."

Du Bois (pronounced

doo-boyz; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American

sociologist,

historian,

civil rights activist,

Pan-Africanist, author, and editor. Born in

Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community. After completing graduate work at the

University of Berlin and

Harvard, where he was the first

African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at

Atlanta University. Du Bois was one of the co-founders of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Du Bois rose to national prominence as the leader of the

Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists who wanted equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the

Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by

Booker T. Washingtonwhich provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the

Talented Tenth and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership.

Racism was the main target of Du Bois's polemics, and he strongly protested against

lynching,

Jim Crow laws, and

discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several

Pan-African Congresses to fight for independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. After World War I, he surveyed the experiences of American black soldiers in France and documented widespread bigotry in the United States military.

Du Bois was a prolific author. His collection of essays,

The Souls of Black Folk, was a seminal work in

African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus

Black Reconstruction in America challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the

Reconstruction Era. He wrote one of the first scientific treatises in the field of American sociology, and he published three autobiographies, each of which contains insightful essays on sociology, politics and history. In his role as editor of the NAACP's journal

The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism, and he was generally sympathetic to socialist causes throughout his life. He was an ardent peace activist and advocated

nuclear disarmament. The United States'

Civil Rights Act, embodying many of the reforms for which Du Bois had campaigned his entire life, was enacted a year after his death.

Early life

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in

Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to Alfred and Mary Silvina (née Burghardt) Du Bois.

[2] Mary Silvina Burghardt's family was part of the very small

free black population of Great Barrington and had long owned land in the state. She was descended from

Dutch,

African and English ancestors.

[3] William Du Bois's maternal great-great-grandfather was Tom Burghardt, a slave (born in

West Africa around 1730), who was held by the Dutch colonist Conraed Burghardt. Tom briefly served in the

Continental Army during the

American Revolutionary War, which may have been how he gained his freedom during the 18th century.

[4] His son Jack Burghardt was the father of

Othello Burghardt, who was the father of Mary Silvina Burghardt.

[4]

William Du Bois's paternal great-grandfather was James Du Bois of

Poughkeepsie, New York, an ethnic

French-American who fathered several children with

slave mistresses.

[5] One of James'

mixed-race sons was Alexander. He traveled and worked in

Haiti, where he fathered a son, Alfred, with a mistress. Alexander returned to Connecticut, leaving Alfred in Haiti with his mother.

[6]

Sometime before 1860, Alfred Du Bois emigrated to the United States, settling in Massachusetts. He married Mary Silvina Burghardt on February 5, 1867, in

Housatonic.

[6] Alfred left Mary in 1870, two years after their son William was born.

[7] Mary Burghardt Du Bois moved with her son back to her parents' house in Great Barrington until he was five. She worked to support her family (receiving some assistance from her brother and neighbors), until she suffered a stroke in the early 1880s. She died in 1885.

[8]

Great Barrington had a majority

European American community, who treated Du Bois generally well. He attended the local integrated public school and played with white schoolmates. As an adult, he wrote about racism which he felt as a fatherless child and the experience of being a minority in the town. But, teachers recognized his ability and encouraged his intellectual pursuits, and his rewarding experience with academic studies led him to believe that he could use his knowledge to empower African Americans.

[9] Du Bois graduated from the town's

Searles High School. When Du Bois decided to attend college, the congregation of his childhood church, the

First Congregational Church of Great Barrington, raised the money for his tuition.

[10]

University education

The title page of Du Bois's Harvard dissertation,

Suppression of the African Slave Trade in the United States of America: 1638-1871

Relying on money donated by neighbors, Du Bois attended

Fisk University, a

historically black college in

Nashville, Tennessee, from 1885 to 1888.

[11] His travel to and residency in the South was Du Bois's first experience with Southern racism, which at the time encompassed

Jim Crow laws, bigotry, suppression of black voting, and

lynchings; the lattermost reached a peak in the next decade.

[12] After receiving a

bachelor's degree from Fisk, he attended

Harvard College (which did not accept course credits from Fisk) from 1888 to 1890, where he was strongly influenced by his professor

William James, prominent in American philosophy.

[13] Du Bois paid his way through three years at Harvard with money from summer jobs, an inheritance, scholarships, and loans from friends. In 1890, Harvard awarded Du Bois his second bachelor's degree,

cum laude, in history.

[14] In 1891, Du Bois received a scholarship to attend the sociology graduate school at Harvard.

[15]

Wilberforce and Philadelphia

"Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: ... How does it feel to be a problem? ... One ever feels his two-ness,–an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder ... He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face."

—Du Bois, "Strivings of the Negro People", 1897[19]

In the summer of 1894, Du Bois received several job offers, including one from the prestigious

Tuskegee Institute; he accepted a teaching job at

Wilberforce University in Ohio.

[20] At Wilberforce, Du Bois was strongly influenced by

Alexander Crummell, who believed that ideas and morals are necessary tools to effect social change.

[21] While at Wilberforce, Du Bois married Nina Gomer, one of his students, on May 12, 1896.

[22]

After two years at Wilberforce, Du Bois accepted a one-year research job from the

University of Pennsylvania as an "assistant in sociology" in the summer of 1896.

[23] He performed sociological field research in Philadelphia's African-American neighborhoods, which formed the foundation for his landmark study,

The Philadelphia Negro,published in 1899 while he was teaching at

Atlanta University. It was the first case study of a black community in the United States.

[24] By the 1890s, Philadelphia's black neighborhoods had a negative reputation in terms of crime, poverty, and mortality. Du Bois's book undermined the stereotypes with experimental evidence, and shaped his approach to segregation and its negative impact on black lives and reputations. The results led Du Bois to realize that racial integration was the key to democratic equality in American cities.

[25]

While taking part in the American

Negro Academy (ANA) in 1897, Du Bois presented a paper in which he rejected

Frederick Douglass's plea for black Americans to integrate into white society. He wrote: "we are Negroes, members of a vast historic race that from the very dawn of creation has slept, but half awakening in the dark forests of its African fatherland".

[26] In the August 1897 issue of

Atlantic Monthly, Du Bois published "Strivings of the Negro People", his first work aimed at the general public, in which he enlarged upon his thesis that African Americans should embrace their African heritage while contributing to American society.

[27]

Atlanta University

In July 1897, Du Bois left Philadelphia and took a professorship in history and economics at the historically black

Atlanta University in Georgia.

[28] His first major academic work was his book

The Philadelphia Negro (1899), a detailed and comprehensive sociological study of the African-American people of Philadelphia, based on the field work he did in 1896–1897. The work was a breakthrough in scholarship, because it was the first scientific study of African Americans and a major contribution to early scientific sociology in the U.S.

[29][30] In the study, Du Bois coined the phrase "the submerged tenth" to describe the black underclass. Later in 1903 he popularized the term, the "

Talented Tenth", applied to society's elite class.

[31] Du Bois's terminology reflected his opinion that the elite of a nation, both black and white, was critical to achievements in culture and progress.

[31] Du Bois wrote in this period in a dismissive way of the underclass, describing them as "lazy" or "unreliable", but he – in contrast to other scholars – he attributed many of their societal problems to the ravages of slavery.

[32]

Du Bois's output at Atlanta University was prodigious, in spite of a limited budget: He produced numerous social science papers and annually hosted the

Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems.

[33] Du Bois also received grants from the U.S. government to prepare reports about African-American workforce and culture.

[34] His students considered him to be a brilliant, but aloof and strict, teacher.

[35]

First Pan-African Conference

At the conclusion of the conference, delegates unanimously adopted the "Address to the Nations of the World", and sent it to various heads of state where people of African descent were living and suffering oppression.

[40] The address implored the United States and the imperial European nations to "acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent" and to respect the integrity and independence of "the free Negro States of

Abyssinia,

Liberia,

Haiti, etc."

[41] It was signed by Bishop

Alexander Walters (President of the Pan-African Association), the Canadian Rev. Henry B. Brown (Vice-President), Williams (General Secretary) and Du Bois (Chairman of the Committee on the Address).

[42]The address included Du Bois's observation, "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the

colour-line." He used this again three years later in the "Forethought" of his book,

The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

[43]

Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

In the first decade of the new century, Du Bois emerged as a spokesperson for his race, second only to

Booker T. Washington.

[44] Washington was the director of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, and wielded tremendous influence within the African-American and white communities.

[45]Washington was the architect of the

Atlanta Compromise, an unwritten deal he struck in 1895 with Southern white leaders who dominated state governments after Reconstruction. Essentially the agreement provided that Southern blacks, who lived overwhelmingly in rural communities, would submit to the current discrimination, segregation,

disenfranchisement, and non-unionized employment; that Southern whites would permit blacks to receive a basic education, some economic opportunities, and justice within the legal system; and that Northern whites would invest in Southern enterprises and fund black educational charities.

[46]

Du Bois was inspired to greater activism by the

lynching of

Sam Hose, which occurred near Atlanta in 1899.

[51] Hose was tortured, burned and hung by a mob of two thousand whites.

[51] When walking through Atlanta to discuss the lynching with newspaper editor

Joel Chandler Harris, Du Bois encountered Hose's burned knuckles in a storefront display.

[51] The episode stunned Du Bois, and he resolved that "one could not be a calm cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved."

[52] Du Bois realized that "the cure wasn't simply telling people the truth, it was inducing them to act on the truth."

[53]

In 1901, Du Bois wrote a review critical of Washington's autobiography

Up from Slavery,

[54] which he later expanded and published to a wider audience as the essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others" in

The Souls of Black Folk.

[55] Later in life, Du Bois regretted having been critical of Washington in those essays.

[56] One of the contrasts between the two leaders was their approach to education: Washington felt that African-American schools should focus primarily on

industrial education topics such as agricultural and mechanical skills, to prepare southern blacks for the opportunities in the rural areas where most lived.

[57] Du Bois felt that black schools should focus more on

liberal arts and academic curriculum (including the classics, arts, and humanities), because liberal arts were required to develop a leadership elite.

[58] However, as sociologist

E. Franklin Frazierand economists

Gunnar Myrdal and

Thomas Sowell have argued, such disagreement over education was a minor point of difference between Washington and Du Bois; both men acknowledged the importance of the form of education that the other emphasized.

[59][60][61] Sowell has also argued that, despite genuine disagreements between the two leaders, the supposed animosity between Washington and Du Bois actually formed among their followers, not between Washington and Du Bois themselves.

[62] Du Bois himself also made this observation in an interview published in the

The Atlantic Monthly in November 1965.

[63]

Niagara Movement

Founders of the

Niagara Movement in 1905. Du Bois is in the middle row, with white hat.

In 1905, Du Bois and several other African-American civil rights activists – including

Fredrick L. McGhee,

Jesse Max Barber and

William Monroe Trotter – met in Canada, near

Niagara Falls.

[64] There they wrote a declaration of principles opposing the Atlanta Compromise, and incorporated as the

Niagara Movement in 1906.

[65] Du Bois and the other "Niagarites" wanted to publicize their ideals to other African Americans, but most black periodicals were owned by publishers sympathetic to Washington. Du Bois bought a printing press and started publishing

Moon Illustrated Weekly in December 1905.

[65] It was the first African-American illustrated weekly, and Du Bois used it to attack Washington's positions, but the magazine lasted only for about eight months.

[66] Du Bois soon founded and edited another vehicle for his polemics,

The Horizon: A Journal of the Color Line, which debuted in 1907.

Freeman H. M. Murray and

Lafayette M. Hershaw served as

The Horizon's co-editors.

[67]

The Niagarites held a second conference in August 1906, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of abolitionist

John Brown's birth, at the West Virginia site of Brown's

raid on Harper's Ferry.

[66] Reverdy C. Ransom spoke and addressed the fact that Washington's primary goal was to prepare blacks for employment in their current society: "Today, two classes of Negroes, [...] are standing at the parting of the ways. The one counsels patient submission to our present humiliations and degradations; [...] The other class believe that it should not submit to being humiliated, degraded, and remanded to an inferior place [...] it does not believe in bartering its manhood for the sake of gain."

[68]

The Souls of Black Folk

In an effort to portray the genius and humanity of the black race, Du Bois published

The Souls of Black Folk (1903), a collection of 14 essays.

[69]James Weldon Johnson said the book's effect on African Americans was comparable to that of

Uncle Tom's Cabin.

[70] The introduction famously proclaimed that "[...] the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line."

[71] Each chapter begins with two epigraphs – one from a white poet, and one from a black spiritual – to demonstrate intellectual and cultural parity between black and white cultures.

[72] A major theme of the work was the

double consciousness faced by African Americans: Being both American and black. This was a unique identity which, according to Du Bois, had been a handicap in the past, but could be a strength in the future: "Henceforth, the destiny of the race could be conceived as leading neither to assimilation nor separatism but to proud, endur.........