Science & Environment

- 22 September 2015

Neil Armstrong will be forever known as the first person to walk on the Moon. But less well known are his early exploits as a test pilot. Armstrong risked life and limb in a variety of experimental vehicles before he became an astronaut - a career that very nearly didn't happen.

In the centre of a large, bright hangar at California's Edwards Air Force Base was a large cross made of two iron girders balanced on a universal truck joint.

Six thrusters on the ends of the cross's limbs shot spurts of compressed nitrogen every time Neil Armstrong, sitting in a makeshift cockpit on the cross's forward end, moved the control stick in his left hand.

It might not have looked it in 1956, but this barebones simulator was the future Moonwalker's first step into space.

Armstrong's love affair with aviation began when he was six years old and skipped Sunday school to take an airplane ride with his father.

Inspired, Armstrong devoured books and magazines about flying, built model airplanes, and eventually earned his private pilot's licence at 16 before he even learned to drive.

In 1947, he began his formal training, enrolling at Purdue University, Indiana, in a four year engineering programme in exchange for three years of service with the US Navy.

It was an interesting time for aviation. Just a month after Armstrong started college, US Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in the rocket-powered Bell X-1.

It seemed to Armstrong that he was entering aviation too late; the aircraft he'd fallen in love with growing up were being replaced by rocket-powered designs, and there were no new records to break. But it was exactly the opposite.

NASA

NASA

The advent of rocket-powered flight opened a new era of flying where aviators had to be both pilots and engineers testing experimental aircraft in real-time in the sky. And the best place for this new breed of pilot-engineer was the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), America's leading body for aviation research.

Degree in hand and three years flying in the Korean war under his belt, Armstrong arrived at the NACA's High Speed Flight Station at Edwards Air Force Base in 1955. He joined four other pilots flying anything from bombers to experimental rocket planes to futuristic simulators. The simulators included the Iron Cross.

Traditional airplanes have flight control surfaces; ailerons, rudders, and elevators move a plane by pushing against the air as it flies. But a rocket plane flying above the atmosphere has no air for these surfaces to push against.

Instead, they used reaction controls, small jets of compressed gas that nudge the airplane in a near-void to maintain its orientation. It was a kind of flying Armstrong needed to learn. He was training to reach the fringes of space in the X-15.

NASA

NASA

The X-15 was a joint NACA-Air Force vehicle incepted not long before Armstrong arrived at Edwards to answer questions about how a man would fare flying hypersonically — faster than Mach 5 or five times the speed of sound — at altitudes so high that landing would be a close comparison to returning from orbit.

Just 15m (50ft) long with a 7m (23ft) wingspan, the X-15 was launched from underneath the wing of a B-52 bomber so it could conserve all its fuel for either a high altitude or a high speed run. Armstrong only flew seven missions in the X-15, reaching a top speed of Mach 5.74 and a peak altitude of 63km (39.2 miles). He didn't reach space — the cutoff of space was set at 80km (50 miles) — but he was already on his way there.

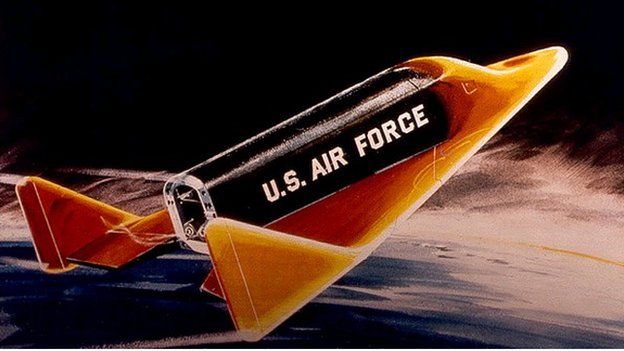

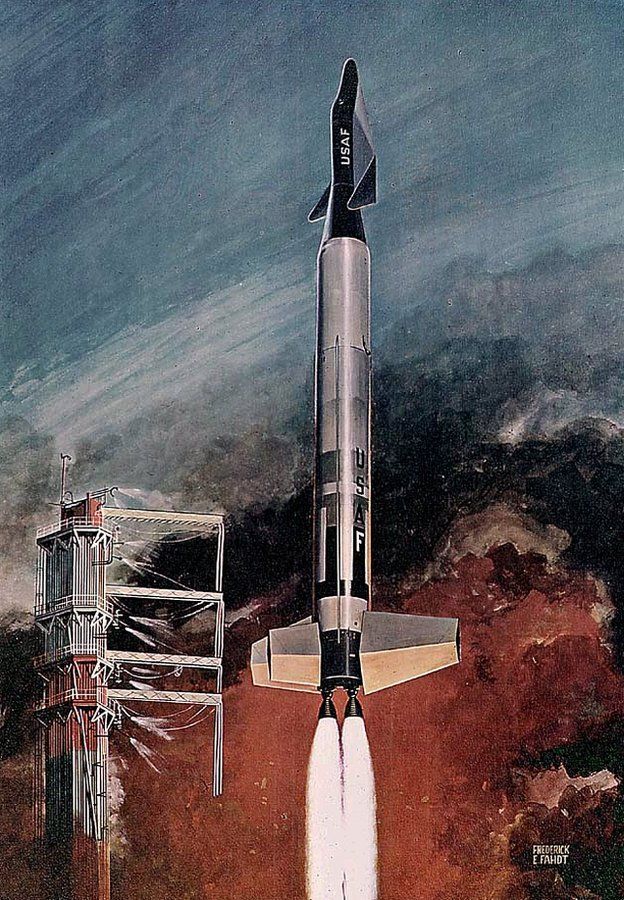

In the early 1960s, the Air Force's next step after the X-15 was to fly in space in a vehicle eventually called Dyna-Soar. Another joint program with the NACA that was transferred to Nasa when it was established in 1958, Dyna-Soar was a flat-bottomed, roughly triangular-shaped glider designed to launch vertically atop a Titan missile.

It would circle the Earth before firing its engines against its direction of travel to start its fall back through the Earth's atmosphere. From there, the pilot would land it like a regular airplane on a runway. And Armstrong was one pilot selected to fly it into space, but first he had to figure out how to save himself and his fellow astronauts from an exploding launch vehicle.

NASA

NASA NASA

NASA

In launch configuration, the Dyna-Soar glider was oriented with its nose up, meaning that if the pilot ejected he would be expelled laterally and his parachute wouldn't have time to open before he hit the ground.

The better option, Armstrong saw, was to use Dyna-Soar's aerodynamics. He reasoned that if the glider's engines could launch it away from an exploding rocket, any skilled pilot would be able to land it safely.

Theory in hand, Armstrong put it to the test. In a Douglas 5FD Skylancer fighter jet modified so that its aerodynamics mimicked the Dyna-Soar's, he flew it low over the desert terrain until he reached a square painted on the ground to represent a launch pad.

At that moment, he pulled the aircraft's nose up to begin a steep climb to about 2,130m (7,000ft), which was roughly the altitude that the Dyna-Soar's engines would carry it to.

NASA

NASA

From there, he did what any pilot would naturally do: he pulled the plane over in a loop and rolled it upright before making a smooth unpowered landing on a strip drawn on the desert floor to represent a runway. It was a manoeuvre Armstrong later said he was happy he never had to fly in a real Dyna-Soar.

Both the X-15 and the Dyna-Soar dealt with technologies ahead of their times, but neither was the most experimental programme Armstrong was involved in while at Edwards.

In the early 1960s, Nasa was keen to move away from ending orbital spaceflights with splashdowns in the ocean; astronauts were accomplished pilots who didn't need an armada of Navy ships to pull them out of the water.

The space agency was researching using a paraglider wing to land the second-generation Gemini spacecraft on a runway at the end of its missions.

This novel landing system caught the attention of Milt Thompson, another test pilot at Edwards who eventually convinced Armstrong to help him build a homemade test vehicle.

More from Science & Environment

NASA

NASA

Armstrong's simple yet brilliant refrain about small steps and giant leaps - its intonation betraying such acute awareness of the historic nature of the moment - remains forever etched into the minds of a generation who witnessed the moon landings first hand.

The pilots' self-guided project was eventually approved as an official programme to spare either man dying in their own creation. With input from others at Edwards, the pair eventually built a barebones paraglider research vehicle called the Parasev.

It took to the skies in 1961 with Thompson in the cockpit towed behind Armstrong in a small airplane, and though the Paresev proved paraglider landings were feasible the system was never implemented.

Though Edwards had been Armstrong's ideal workplace when he arrived in 1955, things changed in April 1962 when Nasa announced it would be selecting a second group of astronauts.

The agency received 253 applications by the 1 June deadline, and a week later Armstrong's was quietly added to the list; a simulation expert from Edwards was so convinced of Armstrong's potential as an astronaut that he added the late application to the pile before the Nasa selection committee's first meeting.

After a series of gruelling medical and psychological tests, Armstrong was selected on 17 September.

It was fortuitous timing. Dyna-Soar, Armstrong's previous ticket to space, was fast falling behind schedule and any Air Force space program was looking increasingly unlikely to leave the ground. As one of Nasa's "New Nine" astronauts, Armstrong was firmly on the path to space.

Amy Shira Teitel is the author of "Breaking the Chains of Gravity," which tells the story of America's nascent space programme before Nasa's creation.

Selected Sources:

James Hansen, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. Simon & Schuster, New York. 2005.

Robert Godwin ed. X-15: The NASA Mission Reports. Apogee, Burlington. 2000.

Robert Godwin ed. Dyna-Soar: Hypersonic Strategic Weapon System. Apogee, Burlington. 2003.

Richard P Hallion. On the Frontier: Flight Research at Dryden, 1946-1981. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington. 1984.

No comments:

Post a Comment