Pleiades

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the star cluster. For other uses of Pleiades or Pléiades, see Pleiades (disambiguation).

| Pleiades | |

|---|---|

| |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Taurus |

| Right ascension | 3h 47m 24s[1] |

| Declination | +24° 07′ 00″[1] |

| Distance | 444 ly on average (136.2±1.2 pc[2][3][4][5]) |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.6[6] |

| Apparent dimensions (V) | 110' (arcmin.)[6] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Other designations | M45,[1] Seven Sisters,[1]Melotte 22[1] |

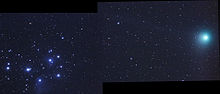

In astronomy, the Pleiades (/ˈplaɪədiːz/ or /ˈpliːədiːz/), or Seven Sisters (Messier 45 or M45), is an open star cluster containing middle-aged hot B-type stars located in the constellation of Taurus. It is among the nearest star clusters to Earth and is the cluster most obvious to the naked eye in the night sky. The celestial entity has several meanings in different cultures and traditions.

The cluster is dominated by hot blue and extremely luminous stars that have formed within the last 100 million years. Dust that forms a faint reflection nebulosity around the brightest stars was thought at first to be left over from the formation of the cluster (hence the alternative name Maia Nebula after the star Maia), but is now known to be an unrelated dust cloud in the interstellar medium, through which the stars are currently passing. Computer simulations have shown that the Pleiades was probably formed from a compact configuration that resembled the Orion Nebula.[7] Astronomers estimate that the cluster will survive for about another 250 million years, after which it will disperse due to gravitational interactions with its galactic neighborhood.[8]

Contents

[hide]Origin of name[edit]

The name of the Pleiades comes from Ancient Greek. It probably derives from plein ('to sail') because of the cluster's importance in delimiting the sailing season in the Mediterranean Sea: 'the season of navigation began with their heliacal rising'.[9] However, the name was later mythologised as the name of seven divine sisters, whose name was imagined to derive from that of their mother Pleione, effectively meaning 'daughters of Pleione'. In reality, the name of the star-cluster almost certainly came first, and Pleione was invented to explain it.[10]

Observational history[edit]

The Pleiades are a prominent sight in winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and have been known since antiquity to cultures all around the world, including the Celts, Māori,Aboriginal Australians, the Persians, the Arabs (who called them Thurayya), the Chinese, the Japanese, the Maya, the Aztec, the Sioux and the Cherokee. In Hinduism, the Pleiades are known as Krittika and are associated with the war-god Kartikeya (Murugan, Skanda), who derives his name from them. The god is raised by the six Krittika sisters, also known as the Matrikas. He is said to have developed a face for each of them.

The Babylonian star catalogues name the Pleiades MUL.MUL or "star of stars", and they head the list of stars along the ecliptic, reflecting the fact that they were close to the point of vernal equinox around the 23rd century BC. The Ancient Egyptians may have used the names "Followers" and "Ennead" in the prognosis texts of the Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days of papyrus Cairo 86637.[11] The earliest known depiction of the Pleiades is likely a bronze age artifact known as the Nebra sky disk, dated to approximately 1600 BC. Some Greekastronomers considered them to be a distinct constellation, and they are mentioned by Hesiod, and in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. They are also mentioned three times in the Bible (Job 9:9 and 38:31, as well as Amos 5:8). Some scholars of Islam suggested that the Pleiades (ath-thurayya) are the star mentioned in the sura (chapter) Najm of the Quran.

In Japan, the constellation is mentioned under the name Mutsuraboshi ("six stars") in the 8th century Kojiki and Manyosyu documents. The constellation is also known in Japan as Subaru (“unite”) and is depicted in the six-star logo and name of the Subaru automobile company. The Persian equivalent is Nahid (pronounced "Naheed").

The rising of the Pleiades is mentioned in the Ancient Greek text Geoponica.[12] The Greeks oriented the Hecatompedon temple of 550 BC and the Parthenon of 438 BC to their rising.[13] The rising of the Pleiades before dawn (usually at the beginning of June) has long been regarded as the start of the new year in Māori culture, with the star group being known as Matariki. The rising of Matariki is celebrated as a midwinter festival in New Zealand.[14] In Hawaiian culture the cluster is known as the Makali'i and their rising shortly after sunset marks the beginning of Makahiki, a 4-month time of peace in honor of the god Lono.

Galileo Galilei was the first astronomer to view the Pleiades through a telescope. He thereby discovered that the cluster contains many stars too dim to be seen with the naked eye. He published his observations, including a sketch of the Pleiades showing 36 stars, in his treatise Sidereus Nuncius in March 1610.

The Pleiades have long been known to be a physically related group of stars rather than any chance alignment. The Reverend John Michellcalculated in 1767 that the probability of a chance alignment of so many bright stars was only 1 in 500,000, and so correctly surmised that the Pleiades and many other clusters of stars must be physically related.[15] When studies were first made of the stars' proper motions, it was found that they are all moving in the same direction across the sky, at the same rate, further demonstrating that they were related.

Charles Messier measured the position of the cluster and included it as M45 in his catalogue of comet-like objects, published in 1771. Along with the Orion Nebula and the Praesepe cluster, Messier's inclusion of the Pleiades has been noted as curious, as most of Messier's objects were much fainter and more easily confused with comets—something that seems scarcely possible for the Pleiades. One possibility is that Messier simply wanted to have a larger catalogue than his scientific rival Lacaille, whose 1755 catalogue contained 42 objects, and so he added some bright, well-known objects to boost his list.[16]

Edme-Sébastien Jeaurat then drew in 1782 a map of 64 stars of the Pleiades from his observations in 1779, which he published in 1786.[17][18][19]

Distance[edit]

The distance to the Pleiades can be used as an important first step to calibrate the cosmic distance ladder. As the cluster is so close to the Earth, its distance is relatively easy to measure and has been estimated by many methods. Accurate knowledge of the distance allows astronomers to plot a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram for the cluster, which, when compared to those plotted for clusters whose distance is not known, allows their distances to be estimated. Other methods can then extend the distance scale from open clusters to galaxies and clusters of galaxies, and a cosmic distance ladder can be constructed. Ultimately astronomers' understanding of the age and future evolution of the universe is influenced by their knowledge of the distance to the Pleiades. Yet some authors argue that the controversy over the distance to the Pleiades discussed below is a red herring, since the cosmic distance ladder can (presently) rely on a suite of other nearby clusters where consensus exists regarding the distances as established by Hipparcos and independent means (e.g., the Hyades, Coma Berenices cluster, etc.).[3]

Measurements of the distance have elicited much controversy. Results prior to the launch of the Hipparcos satellite generally found that the Pleiades were about 135 parsecs away from Earth. Data from Hipparcos yielded a surprising result, namely a distance of only 118 parsecs by measuring the parallax of stars in the cluster—a technique that should yield the most direct and accurate results. Later work consistently argued that the Hipparcos distance measurement for the Pleiades was erroneous.[3][4][5][20][21][22] In particular, distances derived to the cluster via theHubble Space Telescope and infrared color-magnitude diagram fitting favor a distance between 135–140 pc;[3][20] a dynamical distance from optical interferometric observations of the Pleiad double Atlas favors a distance of 133-137 pc.[22] However, the author of the 2007–2009 catalog of revised Hipparcos parallaxes reasserted that the distance to the Pleiades is ~120 pc, and challenged the dissenting evidence.[2]Recently, Francis and Anderson[23] proposed that a systematic effect on Hipparcos parallax errors for stars in clusters biases calculation using the weighted mean, and gave a Hipparcos parallax distance of 126 pc, and photometric distance 132 pc based on stars in the AB Doradus, Tucana-Horologium, and Beta Pictoris moving groups, which are all similar in age and composition to the Pleiades. Those authors note that the difference between these results can be attributed to random error.

The latest result (August, 2014)[24] used very long baseline radio interferometry (VLBI) to determine a distance of 136.2 ± 1.2 pc, thereby claiming "that the Hipparcos measured distance to the Pleiades cluster is in error."

Composition[edit]

The cluster core radius is about 8 light years and tidal radius is about 43 light years. The cluster contains over 1,000 statistically confirmed members, although this figure excludes unresolved binary stars.[25] It is dominated by young, hot blue stars, up to 14 of which can be seen with the naked eye depending on local observing conditions. The arrangement of the brightest stars is somewhat similar to Ursa Majorand Ursa Minor. The total mass contained in the cluster is estimated to be about 800 solar masses.[25]

The cluster contains many brown dwarfs, which are objects with less than about 8% of the Sun's mass, not heavy enough for nuclear fusion reactions to start in their cores and become proper stars. They may constitute up to 25% of the total population of the cluster, although they contribute less than 2% of the total mass.[26] Astronomers have made great efforts to find and analyse brown dwarfs in the Pleiades and other young clusters, because they are still relatively bright and observable, while brown dwarfs in older clusters have faded and are much more difficult to study.

Age and future evolution[edit]

Ages for star clusters can be estimated by comparing the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram for the cluster with theoretical models of stellar evolution. Using this technique, ages for the Pleiades of between 75 and 150 million years have been estimated. The wide spread in estimated ages is a result of uncertainties in stellar evolution models, which include factors such as convective overshoot, in which aconvective zone within a star penetrates an otherwise non-convective zone, resulting in higher apparent ages.

Another way of estimating the age of the cluster is by looking at the lowest-mass objects. In normal main sequence stars, lithium is rapidly destroyed in nuclear fusion reactions. Brown dwarfs can retain their lithium, however. Due to lithium's very low ignition temperature of 2.5 million kelvin, the highest-mass brown dwarfs will burn it eventually, and so determining the highest mass of brown dwarfs still containing lithium in the cluster can give an idea of its age. Applying this technique to the Pleiades gives an age of about 115 million years.[27][28]

The cluster is slowly moving in the direction of the feet of what is currently the constellation of Orion. Like most open clusters, the Pleiades will not stay gravitationally bound forever. Some component stars will be ejected after close encounters with other stars; others will be stripped by tidal gravitational fields. Calculations suggest that the cluster will take about 250 million years to disperse, with gravitational interactions with giant molecular cloudsand the spiral arms of our galaxy also hastening its demise. [29]

Reflection nebulosity[edit]

Under ideal observing conditions, some hint of nebulosity may be seen around the cluster, and this shows up in long-exposure photographs. It is areflection nebula, caused by dust reflecting the blue light of the hot, young stars.

It was formerly thought that the dust was left over from the formation of the cluster, but at the age of about 100 million years generally accepted for the cluster, almost all the dust originally present would have been dispersed by radiation pressure. Instead, it seems that the cluster is simply passing through a particularly dusty region of the interstellar medium.

Studies show that the dust responsible for the nebulosity is not uniformly distributed, but is concentrated mainly in two layers along the line of sight to the cluster. These layers may have been formed by deceleration due to radiation pressure as the dust has moved towards the stars.[30]

Brightest stars[edit]

The nine brightest stars of the Pleiades are named for the Seven Sisters of Greek mythology: Sterope, Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone, along with their parents Atlas and Pleione. As daughters of Atlas, the Hyades were sisters of the Pleiades. The English name of the cluster itself is of Greek origin (Πλειάδες), though of uncertain etymology. Suggested derivations include: from πλεῖν plein, "to sail," making the Pleiades the "sailing ones"; from πλέος pleos, "full, many"; or from πελειάδες peleiades, "flock of doves." The following table gives details of the brightest stars in the cluster:

List[edit]

| Name | Pronunciation (IPA & respelling) | Designation | Apparent magnitude | Stellar classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcyone | /ælˈsaɪəniː/ al-sy-ə-nee | Eta (25) Tauri | 2.86 | B7IIIe |

| Atlas | /ˈætləs/ at-ləs | 27 Tauri | 3.62 | B8III |

| Electra | /ᵻˈlɛktrə/ i-lek-trə | 17 Tauri | 3.70 | B6IIIe |

| Maia | /ˈmeɪə, ˈmaɪə/ my-ə | 20 Tauri | 3.86 | B7III |

| Merope | /ˈmɛrəpiː/ merr-ə-pee | 23 Tauri | 4.17 | B6IVev |

| Taygeta | /teɪˈɪdʒᵻtə/ tay-ij-i-tə | 19 Tauri | 4.29 | B6V |

| Pleione | /ˈplaɪəniː/ ply-ə-nee | 28 (BU) Tauri | 5.09 (var.) | B8IVpe |

| Celaeno | /sᵻˈliːnoʊ/ sə-lee-noh | 16 Tauri | 5.44 | B7IV |

| Sterope, Asterope | /ˈstɛrəpiː, əˈstɛrəpiː/ (ə)-sterr-ə-pee | 21 and 22 Tauri | 5.64;6.41 | B8Ve/B9V |

| — | — | 18 Tauri | 5.66 | B8V |

Possible planets[edit]

Analyzing deep-infrared images obtained by the Spitzer Space Telescope and Gemini North telescope, astronomers discovered that one of the cluster's stars – HD 23514, which has a mass and luminosity a bit greater than that of the Sun, is surrounded by an extraordinary number of hot dust particles. This could be evidence for planet formation around HD 23514.[31]

No comments:

Post a Comment