Chief Falling Cloud

| Battles/wars | World War II |

|---|---|

| Awards |

Ira Hamilton Hayes (January 12, 1923 – January 24, 1955) was a

who was one of the six flag raisers immortalized in the iconic photograph

of the flag raising on Iwo Jima during World War II.

Ira Hayes

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Ira Hayes | |

|---|---|

Marine Corps recruit photo of Hayes in 1942

| |

| Birth name | Ira Hamilton Hayes |

| Nickname(s) | "Chief Falling Cloud",[1] "Chief"[2] |

| Born | January 12, 1923 Sacaton, Arizona, U.S. |

| Died | January 24, 1955 (aged 32) Bapchule, Arizona, U.S.[3] |

| Buried at | Section 34, Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Unit |

|

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | |

On February 23, 1945, he helped to raise an American flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, an event photographed by Joe Rosenthal of the Associated Press. Hayes and the other five flag-raisers became national heroes as a result. In 1946, he was instrumental in revealing the true identity of one of the other pictured Marines, who was killed in action on Iwo Jima. However, Hayes was never comfortable with his fame, and after his service in the Marine Corps, he descended into alcoholism. He died of exposure to cold and alcohol poisoning after a night of drinking on January 23–24, 1955. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery on February 2, 1955.

Hayes was often commemorated in art and film, before and after his death. In 1949, he portrayed himself raising the flag in the motion picture movie, Sands of Iwo Jima. A giant Marine figure of Hayes raising the flag on Iwo Jima with the other five participants is included on the 1954 Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. In 1961, his life story was the subject of the movie The Outsider, starring Tony Curtis as Hayes. The movie inspired songwriter Peter La Farge to write "The Ballad of Ira Hayes", which became popular nationwide in 1964 after being recorded by Johnny Cash. In 2006, Hayes was portrayed by Adam Beach in the World War II movie Flags of Our Fathers.

Contents

[hide]Early life[edit]

Hayes was born in Sacaton, Arizona, a town in the Gila River Indian Community in Pinal County. He was the eldest of six children born to Nancy Hamilton (1901–1972) and Joseph Hayes (1887–1978).[7] The Hayes children were: Ira (1923–1955), Harold (1924–1925), Arlene (1926–1929), Leonard (1927–1952), Vernon (1929–1958), and Kenneth (born 1931).[7] Joseph Hayes was a World War I veteran who supported his family by subsistence farming and it's cotton harvesting.[8] Nancy Hayes was a devout Presbyterian and a Sunday school teacher at the Assemblies of God church in Sacaton.[8]He was remembered by his family and friends as being a shy and sensitive child. Sara Bernal, his first cousin, stated, "[Joseph Hayes] was a very quiet man; he would go days without saying anything unless you spoke to him first. The other Hayes children would play and tease me, but not Ira. He was quiet, and somewhat distant. Ira didn't speak unless spoken to. He was just like his father."[9] His boyhood friend Dana Norris stated, "Even though I'm from the same culture, I could never get under his skin. Ira had the characteristic of not wanting to talk. But we Pimas are not prone to tooting our own horns. Ira was a quiet guy, such a quiet guy."[9] Despite this, Hayes was a precocious child who displayed an impressive grasp of the English language, a language that many Pimas did not know how to speak.[8] He was also a voracious reader, learning how to read and write by age four.[8]

In 1932, the family settled in Bapchule, Arizona, approximately 12 miles northwest of Sacaton.[8] The Hayes children attended grade school in Sacaton and high school at the Phoenix Indian School in Phoenix, Arizona. Esther Monahan, one of his classmates, stated, "Ira wasn't like the other guys. He was shy and never talked to us girls. He was so much more shy than the other Pima boys. The girls would chase him and try to hug him and kiss him, like we did with all the boys. We'd catch the other boys, who enjoyed it. But not Ira. Ira would just run away."[10] Hayes confided to his classmate Eleanor Pasquale after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, that he was determined on serving in the United States Marine Corps.[10] Pasquale stated, "Every morning in school, [the students] would get a report on World War II. We would sing the anthems of the Army, Marines, and the Navy."[11] Hayes completed two years at the Phoenix Indian School and served in the Civilian Conservation Corps in May and June 1942. He worked as a carpenter before enlisting in the service.[12]

US Marine Corps[edit]

World War II[edit]

On December 2, 1942, he joined Company B, 3rd Parachute Battalion, Divisional Special Troops, 3rd Marine Division, at Camp Elliott, California. On March 14, 1943, Hayes sailed for New Caledonia with the 3rd Parachute Battalion which was assigned to Camp Kiser there on March 25 until September 26; the unit was redesignated in April as Company K, 3rd Parachute Battalion, 1st Marine Parachute Regiment[14] of the I Marine Amphibious Corps. The 3rd battalion was shipped to Guadalcanal and remained there until it was sent to Vella Lavella, arriving there on October 14 for occupational duty. On December 4, he landed with the 3rd battalion on Bougainville and fought against the Japanese as a platoon automatic rifleman (BAR man) with Company K during the Bougainville Campaign.[2] The 3rd Parachute Battalion was shipped back to Guadalcanal and he stayed there until sometime in February when the Paramarines were sent back to California. The 1st Parachute Regiment was officially disbanded at Camp Pendleton, California, in February 1944.

Hayes was transferred to Company E, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment of the newly activated 5th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton. Hayes sailed to Hawaii with his company in September for continued training with the 5th division as it trained for the invasion and capture of Iwo Jima.

Raising the flag on Iwo Jima[edit]

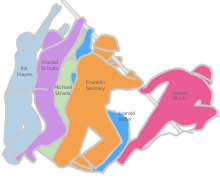

In the early afternoon, Hayes's squad leader, Sergeant Michael Strank, was ordered to take three Marines from his rifle squad in Second Platoon, Easy Company, to bring supplies up Mount Suribachi and raise a larger flag on the summit. Strank chose Corporal Harlon Block, Private First Class Franklin Sousley, and Hayes for the patrol. Marine Private First Class Rene Gagnon, a battalion runner for Easy Company, was ordered up the mountain with the replacement flag. The four Marines together with Gagnon and Private First Class Harold Schultz (Navy corpsman John Bradley was misidentified as a flag-raiser until June 23, 2016),[15] raised the second flag attached onto another steel pipe found by Hayes and Sousley, while at the same time the smaller flag came down. Schultz from Third Platoon, was part of the original 40-man patrol that climbed up Mount Suribachi.

On March 14, another American flag was officially raised at Marine headquarters at the base of Mount Suribachi to signal the Marine occupied Iwo Jima, and the flag on top of Mount Suribachi that Hayes helped to raise there was taken down. Hayes fought on the island until it was secure on March 26, and left Iwo Jima with his unit on March 27. Easy Company had many casualties, Hayes was one of five Marines remaining from his platoon of forty-five men including their corpsmen.[16]

The raising of the second American flag on Mount Suribachi on February 23, 1945 was immortalized by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal and became an icon of the world war. Soon afterwards, the two surviving flag-raisers Hayes and Gagnon, and Bradley who was believed to be in Rosenthal's photograph,[15] became national heroes. Harlon Block who was killed in action on Iwo Jima in March 1945, was misidentified as being Sergeant Henry Hansen from Third Platoon, Easy Company who was also killed in action. Hayes had attempted to correct the misrepresentation of his friend Block for Hansen (Hansen helped raise the first flag) in April 1945, but was silenced by a Marine Corps officer in Washington, D.C. who was placed in charge of the flag-raisers.

7th war bond selling tour[edit]

Hayes and his unit left Iwo Jima on the USS Winged Arrow[2] bound for Hawaii on March 27, 1945. Hayes continued to train at Camp Tarawa again with his unit until April 15, 1945, when he boarded a plane to Washington, D.C. with orders to join C Company, 1st Headquarters Battalion, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C. with the two other surviving second flag-raisers. President Franklin Roosevelt paid for the war by selling war bonds and had requested the flag raisers (in Joe Rosenthal's photograph) participation before he died on April 12. Hayes and Gagnon, and Bradley, were assigned to making public appearances in connection with selling government war bonds for the Seventh War Loan Drive. On April 20, the three met with President Harry Truman at the White House. The bond tour began on May 11 in New York City, after Hayes, Gagnon, and Bradley raised the same flag that was raised on Mount Suribachi, at the Nation's capital during a ceremony at the Capitol steps on May 9. Hayes was in charge of the flag. The bond tour ended on July 4 in Washington, D.C.[17][18] Hayes however, finished his participation in the bond drive on May 24 in Indianapolis, Indiana and returned to Washington, D.C. with orders to rejoin E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines at Camp Tarawa in Hawaii.[2] He arrived at Hilo, Hawaii by plane and rejoined E Company on May 29.On June 19, Hayes was promoted to corporal. He served on occupation duty in Japan with E Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines from September 22 to October 26, 1945. He was honorably discharged from the Marine Corps at Camp Pendleton, California on December 1, 1945. On February 21, 1946, he was awarded a Navy Commendation from the Marine Corps for meritorious service in combat during World War II.

Post World War II[edit]

Ira Hayes (left) with Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron (1947)

Hayes seemed to be disturbed that Harlon Block was still being misrepresented publicly as "Hank" Hansen. One day in 1946, Hayes walked and hitchhiked 1,300 miles from the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona to Edward Frederick Block, Sr.'s farm in Weslaco, Texas, to reveal the truth to Block's family about their son Harlon being in the Rosenthal photograph which led to him being instrumental in having the mistaken second flag-raiser controversy resolved by the Marine Corps in January 1947. Block's family was sincerely grateful to Hayes, especially Harlon's mother who said she knew, from the time she first saw the photo in the newspaper, that it was Harlon in the photo. Mrs. Block took what Hayes said and wrote to her congressman.

In 1949, Hayes appeared briefly as himself in the film Sands of Iwo Jima, starring John Wayne. In the movie, Wayne handed the American flag to Gagnon, Hayes, and Bradley, who at the time were considered the actual three surviving second flag-raisers (the second flag that was raised on Mount Suribachi is used in the film and is handed directly to Gagnon). Hayes was unable to hold on to a steady job for a long period and was arrested 52 times for alcohol intoxication in public at various places in the country including Chicago in October 1953.[20] Referring to his alcoholism, he once said: "I was sick. I guess I was about to crack up thinking about all my good buddies. They were better men than me and they're not coming back. Much less back to the White House, like me."[19] However, he managed to make it sober to the Marine Corps War Memorial dedication on November 10, 1954 where he was lauded by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a hero. A reporter there at the time approached Hayes and asked him, "How do you like the pomp and circumstance?" Hayes hung his head and said, "I don't."[21]

His disquiet about his unwanted fame and his subsequent post-war problems were first recounted in detail by the author William Bradford Huie in The Outsider, published in 1959 as part of his collection Wolf Whistle and Other Stories. The Outsider was filmed in 1961, was directed by World War II veteran turned film director Delbert Mann and starred Tony Curtis as Hayes.[22] The 2006 film Flags of Our Fathers, directed by Clint Eastwood, suggests that Hayes suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder.

Death[edit]

Hayes's headstone in Arlington, Virginia

In the film, The Outsider, his death is dramatized for the screen. He is shown drunk and freezing on a mountain top and unable to climb down. He falls asleep and is shown frozen to death with his arm and hand reaching upwards, like the time he raised the flag on Mount Suribachi. In the song "The Ballad of Ira Hayes", his death is described as dying an indigent death of being drunk and drowning in two inches of water in a ditch.

On February 2, 1955, Hayes was buried in Section 34, Grave 479A at Arlington National Cemetery. At the funeral, fellow flag-raiser Rene Gagnon said of him: "Let's say he had a little dream in his heart that someday the Indian would be like the white man — be able to walk all over the United States."[24]

1993 Marine Corps commemoration[edit]

One of the pairs of hands that you see outstretched to raise our National flag on the battle-scarred crest of Mount Suribachi so many years ago, are those of a Native American ... Ira Hayes ... a Marine not of the ethnic majority of our population.

Were Ira Hayes here today ... I would tell him that although my words on another occasion have given the impression that I believe some Marines ... because of their color ... are not as capable as other Marines ... that those were not the thoughts of my mind ... and that they are not the thoughts of my heart.

I would tell Ira Hayes that our Corps is what we are because we are of the people of America ... the people of the broad, strong, ethnic fabric that is our nation. And last, I would tell him that in the future, that fabric will broaden and strengthen in every category to make our Corps even stronger ... even of greater utility to our nation. That's a commitment of this commandant ... And that's a personal commitment of this Marine.

Military awards[edit]

Hayes' Navy Commendation Ribbon was updated to the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal with Combat "V".[25] He rates the Combat Action Ribbon, for combat in World War II.[26] The large silver star on his Presidential Unit Citation was a Marine Corps, World War II, campaign participation star for Iwo Jima, and does not denote a 2nd Presidential Unit Citation award. Hayes's 16 months of service did not meet the Marine Corps four-year service requirement in World War II for the Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal.Hayes' military decorations and awards:

| Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal with Combat "V" (Navy Commendation Ribbon) | |

| Combat Action Ribbon | |

| Presidential Unit Citation with One 5⁄16 Silver Star (Participation star for Iwo Jima) | |

| American Campaign Medal | |

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Four 3⁄16 Bronze Stars (4 campaigns) | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Navy Occupation Service Medal (Japan) |

Parachutist Badge Parachutist Badge |

Rifle Sharpshooter Badge Rifle Sharpshooter Badge |

U.S. Marine Corps Commendation[edit]

HEADQUARTERS

FLEET MARINE FORCE, PACIFIC

The Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, takes pleasure in COMMENDING, CORPORAL IRA H. HAYES, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS, for service as set forth in the following

CITATION:

For meritorious and efficient performance of duty while serving with a Marine infantry battalion during operations against the enemy on VELLA LAVELLA AND BOUGAINVILLE, BRITISH SOLOMON ISLANDS, from 15 August to 15 December 1943, and on IWO JIMA, VOLCANO ISLANDS, from 19 February to 27 March 1945. Although often under heavy enemy fire, Corporal HAYES carried out his duties during all these campaigns in a highly commendable manner. Regardless of danger of personal fatigue he worked tirelessly, and his efforts greatly aided his unit in accomplishing its assigned missions. His courage, initiative, and loyal devotion to duty continually set an example for all who served with him, and his conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Commendation Ribbon Authorized[2]

- /S/ Roy S. Geiger,

- Lt. General, U.S. Marine Corps

Portrayal in music, film and literature[edit]

Hayes's story was immortalized in a song, "The Ballad of Ira Hayes", by Peter LaFarge. Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Smiley Bates, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Kinky Friedman, Tom Russell, Hazel Dickens, Patrick Sky and Townes Van Zandt each covered the song. In 1964, Cash took the song to number 3 on the Billboard country music chart.[27]Ira Hayes appeared as himself in the 1949 John Wayne film, Sands of Iwo Jima. In the 1960 telefilm The American, he was played by World War II Marine veteran Lee Marvin. Tony Curtis played Hayes in the 1961 film The Outsider.[22] Hayes was portrayed by Adam Beach in the 2006 movie Flags of Our Fathers, directed by Clint Eastwood. The movie was based on the 2000 bestselling book of the same name by James Bradley and Ron Powers.

The poet Ai dedicates her poem "I Can't Get Started" to Hayes. Hayes is mentioned in the poem "Petroglyphs of Serena" by Adrian C. Louis. He was also mentioned briefly in the book "Code Talker" by Joseph Bruchac and was mentioned multiple times in the book "Indian Killer" by Sherman Alexie.

Monuments, memorials, and namings[edit]

Ira Hayes' personal honors include:- Marine Corps War Memorial (Marine flag raising figure), Arlington, Virginia.

- Hayes Peak, the northernmost mountain in the Sierra Estrella, Phoenix, Arizona.

- Ira H. Hayes High School, Bapchule, Arizona [3]

- Ira Hayes Park (statue), Sacaton, Arizona.

- Marine Corps League, Ira Hayes Detachment 2, Phoenix, Arizona.

- American Legion, Ira Hayes Post 84, Sacaton, Arizona.

See also[edit]

- Native Americans and World War II

- PTSD

- Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima

- Shadow of Suribachi: Raising The Flags on Iwo Jima

- Survivor guilt

Bibliography[edit]

- Notes

- Jump up ^ Chief Falling Cloud

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Ira Hayes, Pima Marine, by Albert Hemingway, 1988, ISBN 0819171700.

- Jump up ^ Ira Hayes - Find A Grave.

- Jump up ^ Ó'Riain, Seán (2006-09-01). "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times.

- Jump up ^ "Corporal Ira Hamilton Hayes, USMCR". Who's Who in Marine Corps History. History Division, United States Marine Corps. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- Jump up ^ [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bradley & Powers 2006, p. 38

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bradley & Powers 2006, p. 39

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bradley & Powers 2006, pp. 39–41

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bradley & Powers 2006, p. 41

- Jump up ^ Bradley & Powers 2006, pp. 41–42

- ^ Jump up to: a b California Indian Education: Ira Hayes: O'odham USMC Airborne Warrior

- Jump up ^ Bradley & Powers 2006, p. 42

- Jump up ^ The U.S. Airborne, Attached Units — The U.S. Airborne during World War II, 1st Marine Parachute Regiment [2]

- ^ Jump up to: a b USMC Statement on Marine Corps Flag Raisers, Office of U.S. Marine Corps Communication, 23 June 2016

- Jump up ^ American Indian Heritage Month: Iwo Jima Flag Raiser

- Jump up ^ The Mighty Seventh War Loan: http://www.bucknell.edu/x36352.xml

- Jump up ^ Video: Funeral Pyres of Nazidom, 1945/05/10 (1945). Universal Newsreels. May 10, 1945. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Viola, Herman J.; Campbell, Ben Nighthorse (November 18, 2008). "Fighting the Metal Hats: World War II". Warriors in Uniform: The Legacy of American Indian Heroism. National Geographic. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-4262-0361-9.

- Jump up ^ "Then There Were Two". Time. February 7, 1955.

- Jump up ^ Jeffers, Harry Paul (April 1, 2003). "Ira Hayes". The 100 Greatest Heroes. Citadel Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8065-2476-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Outsider at the Internet Movie Database

- Jump up ^ Bradley & Powers 2006, p. 503

- Jump up ^ Chavers, Dean (2007). Modern American Indian Leaders: Their Lives and Their Work. 1. Edwin Mellen Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-7734-5555-9.

- Jump up ^ The Combat Distinguishing Device (Combat "V") denotes he was "exposed to personal hazard during direct participation in combat" SECNAVINST 1650.1H.

- Jump up ^ The Combat Action Ribbon is a personal award, awarded by the Navy and Marine Corps, retroactive from December 7, 1941: Public Law 106-65--October 5, 1999, 113 STAT 588, Sec 564

- Jump up ^ Cash, Johnny (1977). Cash: The Autobiography. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-072753-6. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- References

- Bradley, James; Powers, Ron (2006). Flags of Our Fathers (2006 ed.). Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-58908-5. - Total pages: 576

- Quiet Hero: The Ira Hayes Story written and illustrated by S. D. Nelson, (Lee & Low Books, 2006) ISBN 978-1-58430-263-6.

- The Outsider and Other Stories, by William Bradford Huie, Panther Books, GB 1961, originally published in the USA 1959, by Signet as Wolf Whistle and Other Stories.

- Hemingway, Albert (1988). Ira Hayes, Pima Marine. University Press of America. ISBN 0819171700.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ira Hayes. |

- USMC. "Corporal Ira Hamilton Hayes, USMCR (Deceased)" (Official Biography). Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Gila River Indian Community official website

- Peter LaFarge Biography

- The Flag Raisers on Iwojima.com

- The Outsider at the Internet Movie Database

- Flags of Our Fathers - Movie

Categories:

- 1923 births

- 1955 deaths

- People from Phoenix, Arizona

- Alcohol-related deaths in Arizona

- American Marine Corps personnel of World War II

- Battle of Iwo Jima

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Native American United States military personnel

- Pima people

- Subjects of iconic photographs

- United States Marines